November 29, 2017

Greater Boston is experiencing a lopsided housing boom, with the iron core of Boston proper accounting for almost all of the region’s new growth as the suburbs drag behind in residential production.

It’s a pattern housing experts have seen coming in the years since the Great Recession. High employment rates and private sector wages, an influx of young adults and retiring Baby Boomers, a low vacancy rate, and the ever increasing desirability of the Commonwealth’s capital are keeping housing supply outpaced by the increases in population and income.

City policies like developer incentives and a more streamlined permitting processes has staved off the 2016 decline in new housing permits, but the balance of luxury and market rate units continues to dwarf the affordable and workforce units.

Boston is on the right track and “deserves particular praise, as is given in the report, for the level of effort and success the city proper is having in meeting the housing crisis,” said Paul Grogan, president of the Boston Foundation, at the Tuesday release of the 15th annual Greater Boston Housing Report Card.

“But they can’t do it alone,” Grogan said, “and unfortunately the commitment of our core city is not matched by really any other community in the metropolitan area, and therefore as long as that remains the case, it’s hard to imagine that we will get a handle on the problem and moderate housing prices the way we need to.”

Cities and towns around the Greater Boston region are expected to issue about 12,900 building permits this year, including houses and apartments. But Boston proper bears the brunt, having granted nearly 60 percent of the housing permits issued for buildings of five or more units and over 41 percent of all new housing permits this year. In the last five years, the city has more than doubled its share of regional permitting.

The foundation’s report echoed city reports that rental prices are leveling off – dropping by between 3 percent— partly because of new units coming into the market and relieving pressure on older stock.

But even if the rents dropped overall, due to new higher-end production, median rents or lower-end rents “may not be significantly impacted,” the report’s authors wrote. “Hence, even as average rents have fallen, the proportion of renters who are housing cost–burdened continued to rise in 2017.”

The average income is about $62,000 a year, said Barry Bluestone, the report’s lead author, but the average annual rent is now $35,500 a year. By 2015, an all-time highs of 52 percent of renter households were paying more than 30 percent of their gross income in rent, and 36 percent of homeowners paid monthly mortgage and tax bills exceeding 30 percent of their gross income.

A single-family home within five miles of the center of Boston has a median price of more than $775,000, and the median condominium is $516,000.

“So, despite whatever progress the region has made in housing production, affordability is a greater problem than ever,” the report’s authors wrote.

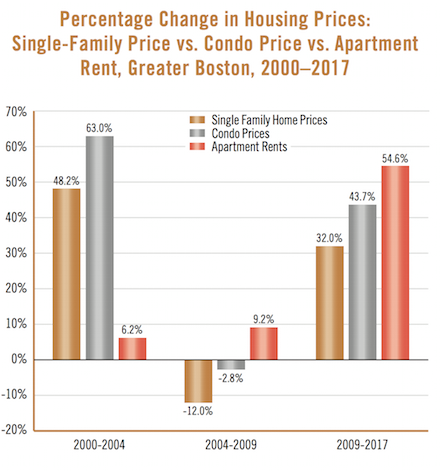

While housing costs in some small suburban communities have retained housing prices near or lower than they were a decade ago, communities nearer to Boston’s core “have seen their home prices explode,” the report finds.

South Boston and Jamaica Plain home prices rose by 83 and 71 percent since 2005. Dorchester is up 40 percent and Roxbury up 29 percent. The rate has increased in recent years, according to the report, especially in historically affordable neighborhoods. While the median cost of housing between 2010 and 2015 increased by 36 percent across the city, it was led by a 70 percent increase in Roxbury, a 52 percent increase in East Boston and a 50 percent increase in Mattapan.

Boston condo sales continue to be highest in South Boston, Dorchester, and Jamaica Plain, according to the report, with South Boston leading the municipal pack in condo sales.

Chrystal Kornegay, undersecretary of Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development, said developers need to work toward self-regulating construction expenses.

“We can’t subsidize our way out of this problem,” she said. She and the city’s housing chief, Sheila Dillon, noted that much of the funding for affordable and middle income construction is coming from leveraging market rate housing through the Inclusionary Development Policy.

“Innovations in construction is key,” Kornegay said. “It’s incredible that we’re at the center of innovation for so many things, but we can’t figure out how to do this better… We can’t continue to build at the prices that we’re seeing now.”

Even in a hot market, builders are limited in what measures they can employ to bring down costs, panelist Joseph Corcoran said Tuesday. “In a development deal, 75 percent of the cost is hard,” he said, “and unless we do something to attack that, we’re not going move too far forward.”

The city’s goal of creating 53,000 new units of housing by 2030 is on track, though Bluestone estimates that three times that amount will be needed across Greater Boston to keep up with the population and job boom.

Suffolk County alone has seen an 8.6 percent increase in population since 2010. The second closest rate of population growth by county is Norfolk, with 5.8 percent, even more dramatic compared to the 1.4 percent growth rate in the balance of the state outside of Greater Boston.

The needed housing inventory just does not exist in the area, Bluestone said.

“At 0.4 percent, the current vacant home inventory in the area is little more than a quarter of the national rate and well below the 2 percent rate usually necessary to stabilize home prices,” the report notes.

And those who cannot afford housing in the urban core are moving into the outlying areas, where housing production is sluggish. A major factor in housing availability is a mismatch between the kinds of residents seeking to live in greater Boston and the traditional housing stock that greets them when they arrive.

These outlying suburbs have been especially weak in building the housing most needed for these new millennial populations -- multi-unit moderately priced apartments and condominium buildings. The report suggests investing in communal village models for young professionals and graduate students, as well as aging Boomers, to lessen their impact on the family-oriented traditional housing around the city.