August 26, 2020

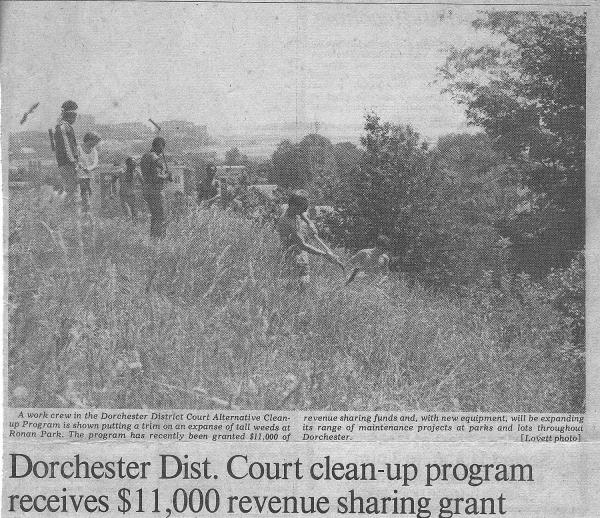

A 1977 news clipping from the now-defunct Dorchester Argus-Citizen showed a work crew landscaping in Ronan Park. Chris Lovett photo

Have you ever noticed white vans parked along the side of highways that carry people who clean the shoulders of highways? The people you see working on the highway grounds are working off fines or sentences as a result of crimes committed.

The program, which operates in many parts of Massachusetts, was initiated at the Dorchester Court in 1976. I was 22 years old at the time, already married, taking classes at UMass Boston, working as a spray painter, and going to community meetings in Dorchester.

At a meeting of the Codman Square Civic Association early in 1976, a resident of Alban Street on Ashmont Hill named Rita Thornton talked about how she had been accosted and had her handbag snatched by a youth who was later apprehended. She was angry but it wasn’t so much at the youth as it was at the Dorchester Court. Her complaint? “You know that kid left the courthouse before I did! What’s he going to learn from that? I’d feel better if they had that kid clean the parks.”

Which struck me as not a bad idea. It just so happened that I had a class the next day at UMass in “Law and Justice” taught by Dorchester Court Judge Jim Dolan, and I brought up what Rita mentioned. I asked if the court had any such program, and he said that they did not, but that it was a “good idea.” I told Judge Dolan that I had just been approved for a summer work-study grant that could be brought into the community, and that “if I were able to get the idea approved, would he be interested in me starting such a program?” He said yes.

So I wrote up a plan and presented it to UMass, which approved it. Later, I walked into the judges’ lobby, located between the major courtrooms in the Dorchester Court building, which was falling apart. Built during the Curley Administration in the 1920s, it was a handsome structure with classically designed courtrooms and a Judges Lobby built to look like the lobby at a Yankee firm in downtown Boston. Some 50 years later, the roof was leaking and the city had given up maintaining it, leaving it with a neglected look.

I asked to speak with Judge Dolan, and I excitedly told him that the idea had been approved by UMass, and asked what would be our next step in implementing it. “I misspoke” Dolan said, “I’m not the presiding justice of the court. You’ll have to speak with Judge Paul King,” whose office was next door to Dolan’s.

Paul King was an interesting person and judge. He was dismissed from the Dorchester Court by the Supreme Judicial Court in 1991 after misconduct that included sexism, racist standards for setting bail, and public drunkenness. But in 1976, he was a reformer who took office during the notoriously corrupt reign of Judge Jerome Troy, who himself had been disbarred and removed from the Dorchester Court in 1973 for lying under oath, using court employees to illegally fill in a creek so he could build a yacht club, and other misdeeds.

The ‘70s were definitely a weird time at the Dorchester Court. Court officers talked about a time when King had to be restrained from beating up Troy, and Judge Dolan talked about a fist fight that broke out in the court hallway – two probation officers duking it out.

Paul King didn’t like young men like me, a college student with long hair, and after I explained the idea of the program, he looked at me and said, “I’m not interested!” I told him that I had a grant, but he reiterated, “Did you hear me? I’m NOT interested.”

I left the court discouraged, and wondered how I could salvage some part of the idea. Then I remembered that a week earlier I had met a 60ish woman named Kit Clark at a Columbia-Savin Hill Civic Association meeting. I told her about some of the things I was involved with, such as trying to start a health center in Codman Square, and she said, “If I can ever be helpful to you, just ask.” I remembered that she worked at Federated Dorchester Neighborhood Houses on Bowdoin Street, in a program that was later named Kit Clark Senior Services.

I walked from the Dorchester Court to the Federated offices on Bowdoin Street and Kit was there. I explained the idea I had, and told her that Judge King had rejected it. I knew that Kit was an important person, but what I didn’t know was that she was the head of Boston’s Republican City Committee and knew everybody in the Republican establishment, which in those days included US Sen. Edward Brooke, former governor Frank Sargent, US Attorney General Elliot Richardson, and many others. I knew that she hosted an annual summer picnic at her home in Savin Hill that attracted nearly every political luminary of either party, and that she was a trustee of UMass Boston. Kit was a powerhouse who wasn’t afraid of taking on anyone, including Judge King.

Kit knew how neglected Boston’s parks had become, and how difficult it was to get them cleaned. She dialed a number on her rotary phone in her office, and said, “I want to speak to Paul King; tell him it’s Kit.” Apparently Kit needed no introduction, and the next think I heard was Kit saying, “This young kid who goes to UMass has an idea that would clean the parks in Dorchester and you said no!?” She engaged in some small talk for a bit, and then hung up the phone and said, “Go back to the court and see Judge King.”

Back at the courthouse, I was again ushered into King’s office. “You didn’t tell me you knew Kit,” he said. I told him he hadn’t asked, and he continued,

“Ok, tell me about this idea.” I explained it was about having the court sentence young people convicted of crimes like vandalism, muggings, stealing cars, etc., to a “Dorchester Court Alternative Clean Up Program,” to work in different parks to do the cleaning. I would run the program, I said. He talked about using a dollar amount that could be worked off. I’m not sure how he set it up, as there wasn’t any money involved. A youth would be found guilty and told that s/he would be fined, say, $100, but that s/he could work it off at $2.50/hour (later $4/hour) in the “clean up program.” My job was to take the youth to various parks in mornings and afternoons and have them work at cleaning the parks. It was a summer job, so I ran it out of my father’s car, and Kit provided rakes and other tools that I brought to sites.

Like too many city buildings, Boston Parks were in horrendous shape in the 1970s. The city was in a financial state of decline, with fewer and fewer parks workers who tended to be political hires and didn’t have to work much, or work hard. With limited grass cutting, trash built up in nearly every Dorchester park. It was also a time when Boston was the auto theft capital of the United States, and cars were regularly burned. At Savin Hill Park, cars were set on fire and pushed off the top of the hill. Between the chaotic environment and the lack of park maintenance, there was a lot of work that could be done.

For me, supervising the program was the perfect job. I saw the program as a way to clean the parks I loved, and I would work alongside the court workers to ensure that lots of work got done. The program quickly became very popular, and we had state reps and city councillors, neighborhood leaders and civic groups calling the court to ask for the court program to clean their parks.

At the end of the summer, during which the Boston Globe did a story on the program, the judge hired me part time to continue the program on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. He added adult workers, especially so-called “non supporters” (those in the court for not supporting children they had fathered), to the group of people allowed to participate in what was renamed the Dorchester Court Alternative Work Program. We had as many as 60 people who would show up on Saturdays to take on Franklin Park’s messy vastness. The program got so large that King appointed two additional supervisors to work with me.

There were so many court workers that I had to make some of the more capable ones “trustees” who would take small groups to certain parts of parks to work. When I completed my studies at UMass Boston in 1977, the judge hired me as a probation officer to continue the program, and added responsibility for the Victims Services unit of the Urban Court Program to my job description.

In 1977, I applied for and received money for a 15-passenger van and a truck to carry the court workers and tools to various sites. We took on the rehabilitation of the Dorchester North Burial Ground, and found gravestones from the 1600s that had been covered by dirt and weeds. I asked some court workers go around and copy the epitaphs on the stones, and we stood up hundreds of gravestones that had been toppled in this horribly neglected historic burial ground.

In the process, we found the three gravestones of enslaved persons that were almost completely buried with only a corner of the headstones sticking up. We got concrete and started trying to piece together some of the horribly vandalized stones. At times we found vaults broken into, with bones and caskets scattered, and it became our job to put the bones back into the vaults and find something to cover the vaults back up. We were told that these vault break-ins were due to rumors that people were buried with their jewelry.

Judge King loved the attention that the program brought to him, and presiding judges at other courts called him to ask about how they could start their own programs. I became an evangelist for the program. Judge Dolan remembers that “the program went from one court to another, and then was picked up by sheriff’s departments.” King and Dolan even occasionally went out with the court workers to parks and vacant lots to clean along with them. Dolan said that King, despite being physically in lots of pain, “worked hard with the court workers.”

In 1980, I left the court and the program to be the first director of the Codman Square Health Center. I told Judge King that leaving was bittersweet, as I enjoyed being able to bring community members involved in the court system into their own community to improve public spaces, spaces that they themselves used. The program spread across the commonwealth in the next decade, which led to the white vans alongside the highways that we see today.

Restitution programs like this have the ability to connect a person convicted of a crime to his actions’ impact on the overall community, and to offer the person an opportunity to make amends to that community while improving it for everyone.