January 30, 2020

Boston is growing — but it’s also graying. And that could have troubling long-term consequences for the lives of the young people who remain.

A report released last week by the Boston Foundation — a non-profit group focused on education and other urban issues — highlighted that and other findings about the changing face of young Boston.

First: that school-aged children — defined as kids from age 5 to 17 — make up a historically small part of Boston’s overall population. In general, that shouldn’t come as too big of a shock: US birth rates are down to historic lows, and many new city-dwellers are childless.

But some of the report’s specific details are striking.

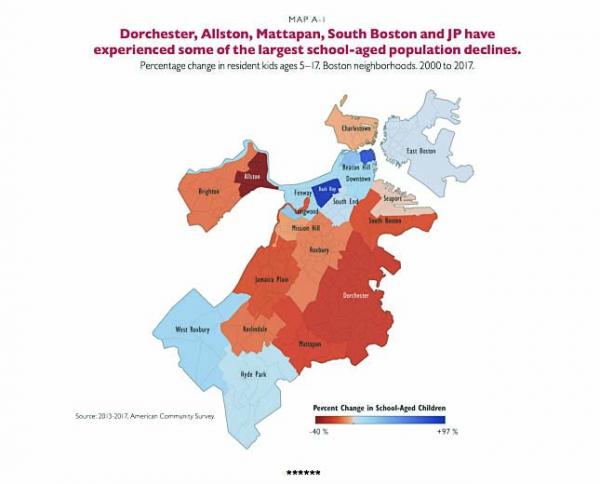

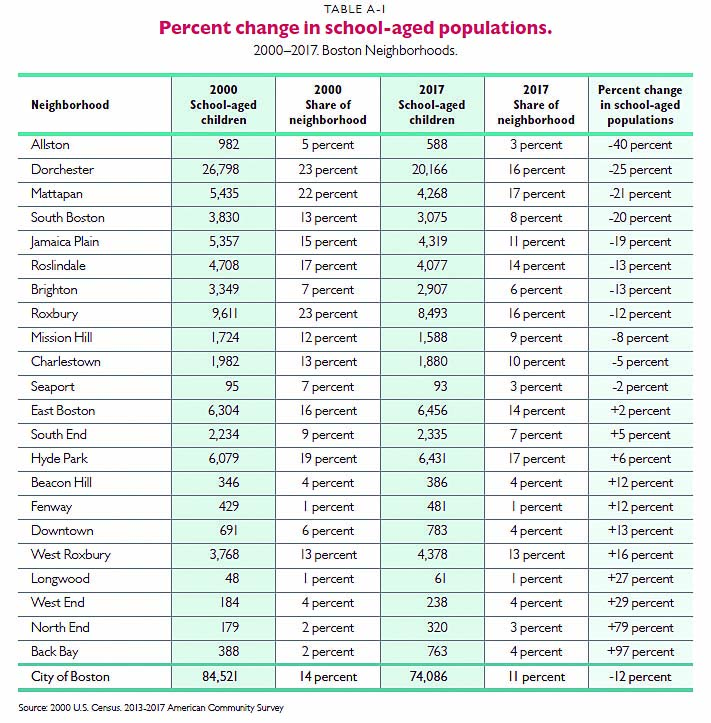

For instance, in 1970, Boston was home to almost 132,000 school-aged children —almost 21 percent of the city’s population. But the latest American Community Survey estimated in 2018 that there were around 75,000 children in Boston — just under 11 percent of the population.

Luc Schuster, director of the Boston Indicators research project, said that the decline took place in “two distinct phases.”

The first phase began in the 1970s, “coinciding with the [court-ordered] desegregation” of schools, said Schuster, who co-authored the report: “One of the ways families were able to avoid participating in school-integration efforts was just to pick up and leave the city.”

But then came another sharp decline in the early 2000s, when the cost of housing started to rise. Since then, Schuster said, “it’s just become harder and harder for middle-income families to make ends meet and stay.”

The report suggests that it was largely white, affluent students who left Boston in the first phase, while thousands of black families took part in the second wave.

The long-term result has been a radical realignment of Boston’s social organization. Since 1980 the city has lost nearly 6,000 middle-income households with children — and gained nearly 25,000 high-income households without children.

That, too, tracks with the general deterioration of the American middle class. But in Boston, it has meant that severe inequalities of race and income are only magnified in its public schools.

Schuster described Boston’s growing racial and ethnic diversity — driven in no small part by new immigration — as one of the bits of “good news” in the city’s recent history.

But the change has not translated to diverse schools. In fact, the report’s data show that two-thirds of BPS students now attend “intensely segregated” schools, where students of color make up 90 percent or more of the total enrollment.

And while Boston’s schools have been improving in recent years by a number of metrics, the report’s data suggest that about half of the city’s middle- and high-income families still move out of Boston when their child turns five (though the report warns that finding is based on “very rough estimates.”)

“The research is really clear that kids benefit tremendously from attending well-integrated public schools,” Schuster said, mentioning academic as well as social and psychological effects. “The concern for Boston is that we’ve set up a school system that concentrates kids — not just by race, but also by income.”

That means opportunity costs, not just for the black and Latino enrollment of BPS, but also for the largely white enrollments in suburban schools.

In a statement, City Councillor Andrea Campbell called the Boston Foundation report a “wake up call.”

“One of the most troubling findings in this report is the plummeting enrollment among black families — who account for 84 percent of the decrease in enrollment,” she wrote. “We shouldn’t be surprised by this, when, for example, roughly 80 percent of students in downtown Boston attend high-quality schools compared with only 5 percent of students in Mattapan; when housing costs are on the rise; and, when there’s been a failure to effectively address our most pressing structural and systemic inequities in BPS ... .”

The Boston Foundation report stops short of proposing solutions about what can feel like a slow-moving crisis. But Schuster himself said he was optimistic about Mayor Marty Walsh’s efforts to grant universal access to childcare in the city. He added that expanded access to moderately-priced housing for the middle class “could help a lot.”

The report serves as a reminder that around 1950, Boston was home to more than 800,000 people. Even after a period of sustained growth, the city is still more than 100,000 people short of that historic high — and so has much more room to grow.

This article was first published on the website of WBUR 90.9FM on Jan. 22. The Reporter and WBUR share content through a media partnership.