September 9, 2020

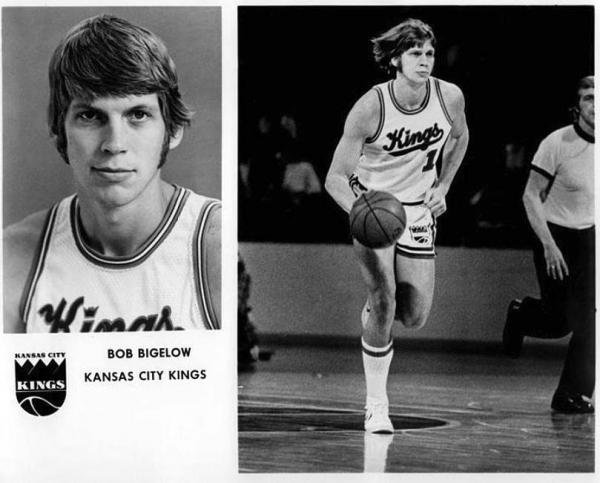

Bob Bigelow

“Big-e-low, Big-e-low, Big-e-low.” The chants echoed loudly throughout the game from the young black kids who watched from the perimeter of the cavernous Washington Park skating rink that was transformed into a basketball court for the summer.

‘Those cheers celebrated the play of Bob Bigelow of Winchester, who had come to the city in the early ’70s to test his roundball mettle against the legendary lineup of the best players in New England: Bill Raynor, King Gaskins, Ron Lee, Steve Strother, Bobby Carrington, Carlton Smith, Will Morrison, Billy Collins, Twinkie Brown, Richard Winslow, Ralph Monteiro, Owen Wells and “Durag.”

And had I said “inner city,” instead of just “the city,” there would be no need to point out that all of those players are black.

So it was a huge deal that “Big,” as he was appropriately known, was standing out so starkly in such august company on the somewhat slippery surface of the court next door to the Shelburne Center, aka the house that Alfreda Harris built. His was not the typical “city game” of feint and flash and finish. To quote JoJo White when he competed in the old NBA HORSE half-time show: It was “Straight in, Mendy” all the way with Big.

As fundamentally sound as the Big “O,” but with blond hair, a loping country boy gait, and a booming voice that accentuated his “bigness,” Bob’s talent eventually made him a first round pick in the NBA. And his love for the game – all games – made him a highly sought-after speaker on the youth sports circuit, where he admonished all of us parents to “just let the kids play.”

So when we recently learned that Bob Bigelow had suddenly passed from this earth, it was beyond stunning. As our close friend Bill Raynor said when I called him to share our grief and disbelief, “The cat had no vices and was the healthiest person I knew; it doesn’t make any sense”.

Within the context of where we’ve come as a city, and where we need to go as a country, Bill also recalled the lobbying that he and Jack McMahon did at the Bigelow family kitchen table to convince Bob’s father that it would be okay, i.e., “safe,” for Bob to play in Roxbury.

It was a necessary pitch because the city at that time was distinctly chopped up into neighborhoods that were only safe for certain kinds of people to be in at certain times. You simply did not go where you didn’t “belong.”

But if the vehicle for crossing that boundary was sports, and basketball in particular, then athletic visas were distributed with de facto enthusiasm. I admittedly view that time, which was not without its significant troubles, with a measure of nostalgia, but more importantly, within the context of sports, as a connector, as a bridge in a world that is now too often painted in irrevocably contrasting colors of black and white. It does not have to be cast in such a bold dichotomy, and sports can help us see ourselves and others through a healthier prism.

I would argue that a turning point (and, yes, we have much more to do together) in Boston’s sometimes discordant attempt to achieve authentic racial harmony had its roots in basketball.

Aside from their innate decency, the fact that Mel King and Ray Flynn played ball together put them in a different place when they conducted a mayoral campaign in 1983 that could have torn the city apart. But their mutual respect and shared love of the city instead put us on a restorative path. Was it all about hoops? Of course not, but, as both men have attested, it certainly didn’t hurt.

Fast forward to the high-profile athletes who today seek to counter the voices of division with their own expressions of unified concern about where we’ve been and where we need to go, and it is clear that their collective impact holds promise. After all, more people know which playoff games have been postponed than know who has been on the podium at either political convention. That is real, enduring impact.

With the excruciating loss of lives and livelihoods that the pandemic has wrought, the loss of sports may seem irrelevant, but I would argue that the relevance of sports as a celebration of mutual respect is a damn good starting point for where we need to go as a society, governed by that one basic indicator on our elementary school report cards of days gone by that pointedly assessed our “Respect for the Rights of Others.”

Let’s start there.

Kevin McCluskey is the associate director of Athletics at UMass Boston and past president of the Boston School Committee.