October 22, 2020

The morning rush hour on Massachusetts highways is unlikely to return to pre-COVID levels until at least 2024, and even more drivers may not return to the fray if economic recovery drags or if working from home remains common, according to new Department of Transportation projections.

That might come as good news to commuters who are enjoying this pandemic-inflicted stretch with fewer cars on the road, but it’s bad news for the MBTA, which attracts a significant chunk of its riders by offering an alternative to grinding congestion.

The new multi-year traffic and ridership models MassDOT developed and presented Monday prompted the MBTA to downgrade its already-strained financial outlook, placing even more pressure on decision-makers as they prepare to implement a package of service cuts almost guaranteed to be unpopular.

The new models, built using Moody’s Analytics economic forecasts, Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys, and travel data, outline three potential scenarios for transportation trends in Massachusetts:

One in which public behaviors gradually return to pre-COVID conditions: a second in which telecommuting remains common even as more businesses resume physical operations; and a third in which the pandemic’s economic damage lingers.

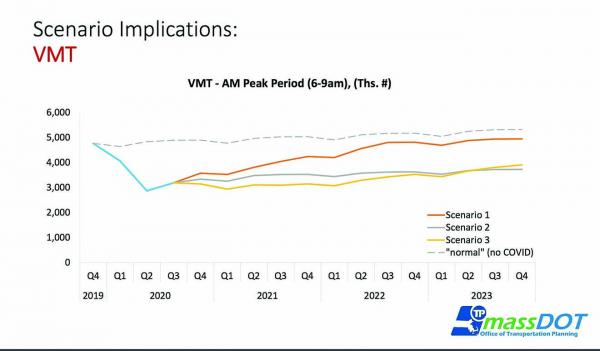

Under all three forecasts, the total vehicle miles traveled during the 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. peak — a way of counting how many cars are on the road for the morning rush — will remain below projections for a hypothetical non-COVID world through the end of 2023.

“This is not saying that [the situation] will never get back to where it was in terms of total, but we’re saying in all of these scenarios, we don’t have the same kind of morning congestion that we used to have because of the combination of economic changes and travel changes,” Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack said at a Monday board meeting.

Wherever the trend lands, its divergence from pre-pandemic expectations carries implications for the state’s attempts to rein in congestion dubbed worst in the nation, greenhouse gas emissions, and public transit.

“Let’s be honest: One of the factors that attracts people to transit is that they are trying to avoid morning rush-hour traffic,” Pollack said. “If morning rush-hour traffic is substantially lower than it was in 2019, that could have knock-on effects in terms of how quickly transit ridership comes back.”

Seven-plus months into the public health crisis, MBTA use – and with it, fare revenue – is at a fraction of its earlier levels. Bus ridership is at about 40 percent of pre-pandemic levels, while the subways have seen about 25 percent of former crowds and commuter rail remains the lowest at around 12 percent.

None of the three scenarios developed by MassDOT expect full crowds to return to public transit for at least several years. Depending on commuter behaviors and health trends, they instead project crowds peaking by June 2022, the end of fiscal year 2023, at 60 percent to 80 percent of past averages.

T officials have been hopeful that ridership patterns will start trending upward next year, but at Monday’s meeting, the agency’s chief financial officer, Mary Ann O’Hara, said fare revenue assumptions built into the FY21 budget adopted in May were “too optimistic.”

Instead of ending the current spending year about $2 million in the black, the MBTA now expects it will wrap up FY21 between $18 million and $46 million in the red — a figure that would have been worse if the budget had not run $36 million better than projections through August.

The longer-term outlook is also declining. Based on the ridership models MassDOT produced, O’Hara told the T’s oversight board that fare revenues could drop another $114 million to $271 million below the existing expectations for fiscal year 2022, amounts that could increase the agency’s deficit by half or more.

“In the past, the T has weathered significant challenges to its operating and capital budgets, but never one of this magnitude,” MBTA General Manager Steve Poftak said in a video to riders the T tweeted on Monday.

Gov. Baker’s revised FY21 state budget would direct about $59 million more to the T than transit officials expected, so that could help solve this year’s shortfall. O’Hara said the organization can also address the gap by reallocating about $80 million in federal formula funding.

Both solutions, though, cut into the resources available for the next fiscal year, when the T expects it could face a massive deficit of anywhere from $308 million to $577 million, leaving more of a gap that will need to be filled with outside aid, service cuts, or fare hikes.

Local elected officials have been vocal about the damage that MBTA service cuts would inflict, and a coalition wants state lawmakers to step in and revive transportation-related taxes to help stave off the damage.

Despite those pleas, Beacon Hill has been virtually silent since legislative leaders agreed nearly three months ago to extend formal lawmaking sessions beyond their traditional July 31 expiration.