November 19, 2015

Olde entrance: The entrance to the Dorchester North Burying Ground in Uphams Corner. James Hobin photoOccasionally, while traveling between one part of Dorchester and another, I get the feeling that I am a particle in a giant subterfuge, colliding with countless other particles spinning in the great hubbub. Time seems to be speeding up; the pace is relentless. But there is a place in Dorchester where stillness reigns, and time is stopped. Once inside the gates of the Dorchester North Burying Ground, the pieces in the kaleidoscope fall away and we are left to contemplate intimations of immortality.

Olde entrance: The entrance to the Dorchester North Burying Ground in Uphams Corner. James Hobin photoOccasionally, while traveling between one part of Dorchester and another, I get the feeling that I am a particle in a giant subterfuge, colliding with countless other particles spinning in the great hubbub. Time seems to be speeding up; the pace is relentless. But there is a place in Dorchester where stillness reigns, and time is stopped. Once inside the gates of the Dorchester North Burying Ground, the pieces in the kaleidoscope fall away and we are left to contemplate intimations of immortality.

The area was laid out in 1634, four years after the arrival of the first wave of English settlers. The site grew to its present dimensions of 3.27 acres and exists as a miniature pastoral idyll with gently rolling hillocks framed by majestic trees, neatly dovetailed into the dense working class neighborhood that has sprung up around it.

In 1869, a Boston publisher printed a compilation of epitaphs prefaced with this statement: “In the old barying-ground at Upham’s Corner, Dorchester, Mass., can be found the most ancient tomb-stone inscriptions in the United States, those at Jamestown, Va., alone being excepted.”

EpitaphThere are about 1,200 stone markers in the cemetery. Looking for the newest, I found one granite marker with the date 1966. The oldest belongs to Mr. Barnard Capen, who died on Nov. 8, 1638, aged 76 years. His gravestone is now housed in the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The next oldest, located close to the intersection of Columbia Road and Stoughton Street, covers the resting spot of two children, their separate stones fit together to carry this enigmatic epitaph:

EpitaphThere are about 1,200 stone markers in the cemetery. Looking for the newest, I found one granite marker with the date 1966. The oldest belongs to Mr. Barnard Capen, who died on Nov. 8, 1638, aged 76 years. His gravestone is now housed in the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The next oldest, located close to the intersection of Columbia Road and Stoughton Street, covers the resting spot of two children, their separate stones fit together to carry this enigmatic epitaph:

“Abel his offering accepted is his body to the grave his soule to blis on octobers twentye and no more in the yeare sixteen hundred 44 Submite submitted to her heavenly king being a flower of that aeternal spring neare 3 years old she dyed in heaven to waite the year was sixteen hundred 48”

•••

Most gravestones have a rounded top wherein images of weeping willows, urns, the hourglass, a skull with wings, or staring human faces have been carved in relief. Though the level of craft varies, the hand of the artisan who did the carving is always evident. Spelling errors are frequent, and even names are spelled incorrectly sometimes, but these details seem to be of no importance.

The earliest gravestones were fashioned from slate that had been quarried in what is now South Boston. I paused to admire one of a later variety, a handsome piece of brown sandstone with square corners. Carved with great skill, the rendering of line was accomplished with exquisite beauty. The sun reflected off the smooth stone surface in contrast to finely cut letters that split the light in grooves, casting shadows that were crisp and strong.

Many inscriptions are presented in Latin, as in the case of Mr. John Foster, the ingenious mathematician and Printer, died 1681, age 33. A graduate of Harvard, Foster, besides having designed the arms of Massachusetts, had written a dissertation on comets. His epitaph is translated as follows:

“Thou O Foster who on earth

didst study The Heavenly Bodies

Now ascend above the firmament.”

On his footstone is inscribed,

“Ars illi sua census erat” (Skill was his cash).

•••

William Pole, who died in 1674 at age 81, was an ancient schoolmaster who wrote his own epitaph, an admonition as sharp as the chisel that first cut his words into stone:

Ho Passenger! Its worth thy pains to stay,

And take a dead man’s lesson by the way.

I was what now thou art, and thou shalt be

What I am now, what odds ‘twixt me and thee.

Now go thy way. But stay, take one word more,

Thy staff, for aught thou knowst, stands next the door

Death is the door, the door of heaven and hell:

Be warn’d, be arm’d, believe, repent, farewell!

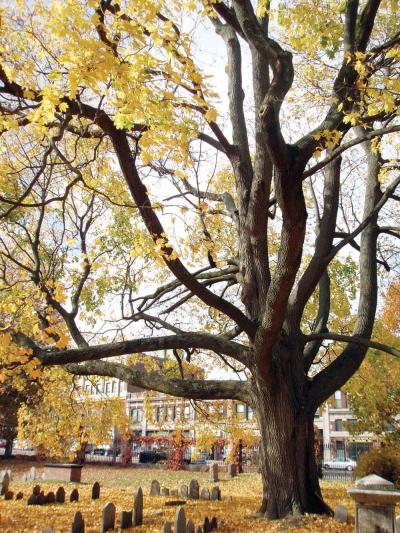

Dorchester's North Burial Ground: This maple tree embraces the burial ground. James Hobin photoNear the center of the cemetery stands a maple tree that would require three people joining hands to encircle its trunk. This one tree seems to reach all corners of the lot, encompassing all things inside, even as the surrounding gravestones recede in proportion to the mighty, far-flung branches. At the base of the tree are three tiny stones, each less than 12 inches tall.

Dorchester's North Burial Ground: This maple tree embraces the burial ground. James Hobin photoNear the center of the cemetery stands a maple tree that would require three people joining hands to encircle its trunk. This one tree seems to reach all corners of the lot, encompassing all things inside, even as the surrounding gravestones recede in proportion to the mighty, far-flung branches. At the base of the tree are three tiny stones, each less than 12 inches tall.

Over time, the tree has shifted, spreading roots that grew into and around the three stones, tugging them closer and lifting them up in a recombination of spirit, stone, and wood. Who is this family? What story can be read in the sequence of their passing? We may know nothing, except that they were loved:

“Cambridge, a negro boy belonging to Robert Oliver, Esq. aged 3 years He died Dec. 14 1747” … “Betty, a negro Servant of Col. Robert Oliver, Died Feb 19, 1748 aged About 25 years” … “Bristol, a Negro Servant of Mr. John Foster Died June 24 1748 aged About 30 yea.”

•••

Dorchester has its share of war memorials, but the oldest, by far, is the tribute to 40 soldiers (all unknown) of the Revolutionary War near the eastern edge of the Burying Ground. There, a slab of grey puddingstone is affixed with a bronze tablet:

“In memory of soldiers of the revolution

Who died during the siege of Boston

And were buried in this lot

1775 – 1778”

•••

The late 1700s brought a change of tone in the epitaphs, with less of the austere piety of the fore fathers, and more of the melancholy pronouncements of succeeding generations. Here is one excerpt from a gravestone inscription made during this period:

“How loved, how valued once, avails thee not,

To whom related, or by whom begot.”

•••

The first gravestones were small and humble. Of course, as people prospered, the gravestones got larger and more information was added. Here is an epitaph from 1833 that needs no introduction:

“This grave was dug and finished in the Year 1833 by Daniel Davenport, when he had been Sexton in Dorchester twenty seven years, had attended 1135 funerals, and dug 734 graves. As Sexton with my spade I learned To delve beneath the sod; Where body to the earth returned, But spirit to its God. Years twenty seven this toll I bore, And midst deaths oft was spared Seven hundred graves and thirty four I dug Then mine prepared.

And when at last I too must die Some else the bell will toll;

As here my Mortal relics lie, May heaven receive my soul.”

•••

Some inscriptions read like short stories as they recount events from the life of the deceased. The following was copied from the epitaph of a man who suffered due to his inability to adapt to the increasingly rapid pace of urbanization:

“Beloved, honoured, and affectionately

remembered by all who knew him. He was

born in Charlestown Dec.10 1758, graduated

at Harvard in 1771, he died in Dorchester

Feb 16, 1837: in consequence of wounds from having been run over by a milk-cart on the 28th of August, 1830. He bore his sufferings with exemplary patience and closed an

irreproachable life with a peaceful death.”

•••

The gravestones give testament to many other tragedies. One tripartite version chronicles a loss on Christmas, and three young men buried together, ages 17, 20, and 28.

“Who returning from Boston on the eve of December 24, 1803 to Dorchester point were drowned by the oversetting of the boat.”

“Soon we all ingulfed must be.

A sudden fate – no warning given –

In the ocean of Eternity. ”

•••

Finally, I would like to paraphrase one last epitaph that might be apropos:

“He hath done what he could.”

Villages: