July 3, 2013

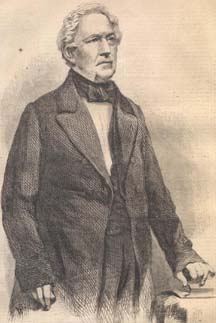

Edward Everett: Dorchester statesman who delivered the Gettysburg oration that preceded Lincoln's address in Nov. 1863.

Edward Everett: Dorchester statesman who delivered the Gettysburg oration that preceded Lincoln's address in Nov. 1863.

(Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the Reporter in July 2013 to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Today is the anniversary of the dedication of the National Cemetery at the site of the battle— and of Abraham Lincoln's celebrated "address.")

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the momentous Battle of Gettysburg— the largest and costliest engagement in our Civil War, a conflict that cost more than 600,000 lives north and south and, ultimately, resulted in the forcible expulsion of the vile institution of slavery from the Republic.

The three-day battle in and around the Pennsylvania crossroads hamlet of Gettyburg stymied a Confederate invasion of the north, marking the “high-water mark” of Rebel ambitions for a victory in their war of secession. The pitched combat cost both sides dearly— resulting in some 50,000 casualties, including 8,000 dead.

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln was on hand to dedicate the first-ever National Cemetery on the grounds of the Gettysburg battlefield. Lincoln’s two-minute speech so eloquently summed up the war’s place in our national history that it sits high atop a tall column of documents enshrined in our national conscience. Lincoln’s address is revered and remembered through the ages as one of our founding documents, though it came some ‘Four score and seven years” after the Constitution was minted.

Before Lincoln rose to speak, another prominent statesmen held the rapt attention of the crowd for some two hours. The speaker was the esteemed Edward Everett of Dorchester, Mass— a former Secretary of State, US Senator, Masachusetts governor and Harvard president who was regarded in his day as the nation’s finest orator.

Following Lincoln’s remarks from the Gettysburg platform, Everett was heard to say: “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

Everett — who had himself run for vice-president in 1860 on a rival ticket to Lincoln's — had since become a political supporter of the president. He asked Lincoln for his own copy of the 272-word speech. Lincoln dutifully obliged and today that “Edward Everett copy” of the address is one of five known “original” copies made in Lincoln’s own hand. The document resides at the the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois.

While Everett’s speech is all but forgotten today, there are elements of his work that hold value today. Unlike later Gettysburg “reunion” events, which sought to honor both sides without judgment or triumphalism, Everett painted a stark contrast between the Union men who were interred before him in the new Soldier’s cemetery and the treasonous southern secessionists who brought such carnage and upheaval upon the land. As Everett spoke, of course, the war’s outcome was not yet secure and some of the most awful bloodlettings of the conflict still lay ahead in places like Cold Harbor, Spotsylvania and Petersburg.

Everett died at age 71 in January 1865 — before he could see Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse or the death of the man whose words came to outshine his own at Gettysburg. Everett is memorialized in his hometown with a bronze statue that stands now off Columbia Road, just steps from the site of his boyhood home in what we still call Edward Everett Square.

Here, below, are some excerpts from Everett’s oration at Gettysburg:

“We have assembled, friends, fellow citizens, at the invitation of the Executive of the great central State of Pennsylvania, seconded by the Governors of seventeen other loyal States of the Union, to pay the last tribute of respect to the brave men who, in the hard-fought battles of the first, second, and third days of July last, laid down their lives for the country on these hillsides and the plains before us, and whose remains have been gathered into the cemetery which we consecrate this day. As my eye ranges over the fields whose sods were so lately moistened by the blood of gallant and loyal men, I feel, as never before, how truly it was said of old that it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country. I feel, as never before, how justly, from the dawn of history to the present time, men have paid the homage of their gratitude and admiration to the memory of those who nobly sacrifice their lives, that their fellow-men may live in safety and in honor. And if this tribute were ever due, to whom could it be more justly paid than to those whose last resting-place we this day commend to the blessing of Heaven and of men?

“For consider, my friends, what would have been the consequences to the country, to yourselves, and to all you hold dear, if those who sleep beneath our feet, and their gallant comrades who survive to serve their country on other fields of danger, had failed in their duty on those memorable days. Consider what, at this moment, would be the condition of the United States, if that noble Army of the Potomac, instead of gallantly and for the second time beating back the tide of invasion from Maryland and Pennsylvania, had been itself driven from these well-contested heights, thrown back in confusion on Baltimore, or trampled down, discomfited, scattered to the four winds. What, in that sad event, would not have been the fate of the Monumental City, of Harrisburg, of Philadelphia, of Washington, the Capital of the Union, each and every one of which would have lain at the mercy of the enemy, accordingly as it might have pleased him, spurred by passion, flushed with victory, and confident of continued success, to direct his course?...

“I allude to these facts, not perhaps enough borne in mind, as a sufficient refutation of the presence, on the part of the Rebels, that the war is one of self-defence, waged for the right of self-government. It is in reality a war originally levied by ambitious men in the cotton-growing States, for the purpose of drawing the slaveholding Border States into the vortex of the conspiracy, first by sympathy, — which in the case of Southeastern Virginia, North Carolina, part of Tennessee, and Arkansas succeeded, — and then by force, and for the purpose of subjugating Maryland, Western Virginia, Kentucky, Eastern Tennessee, and Missouri; and it is a most extraordinary fact, considering the clamors of the Rebel chiefs on the subject of invasion, that not a soldier of the United States has entered the States last named, except to defend their Union-loving inhabitants from the armies and guerillas of the Rebels…

“And now, friends, fellow-citizens, as we stand among these honored graves, the momentous question presents itself, Which of the two parties to the war is responsible for all this suffering, for this dreadful sacrifice of life, — the lawful and constituted government of the United States, or the ambitious men who have rebelled against it? I say “rebelled” against it, although Earl Russell, the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in his recent temperate and conciliatory speech in Scotland, seems to intimate that no prejudice ought to attach to that word, inasmuch as our English forefathers rebelled against Charles I. and James II., and our American fathers rebelled against George III. These certainly are venerable precedents, but they prove only that it is just and proper to rebel against oppressive governments. They do not prove that it was just and proper for the son of James II. to rebel against George I., or his grandson Charles Edward to rebel against George II.; nor, as it seems to me, ought these dynastic struggles, little better than family quarrels, to be compared with this monstrous conspiracy against the American Union.

“ I call the war which the Confederates are waging against the Union a “rebellion,” because it is one, and in grave matters it is best to call things by their right names. I speak of it as a crime, because the Constitution of the United States so regards it, and puts “rebellion” on a par with ‘invasion.’ The constitution and law, not only of England, but of every civilized country, regard them in the same light; or rather they consider the rebel in arms as far worse than the alien enemy. To levy war against the United States is the constitutional definition of treason, and that crime is by every civilized government regarded as the highest which citizen or subject can commit…

“Pardon me, my friends, for dwelling on these wretched sophistries. But it is these which conducted the armed hosts of rebellion to your doors on the terrible and glorious days of July, and which have brought upon the whole land the scourge of an aggressive and wicked war, — a war which can have no other termination compatible with the permanent safety and welfare of the country but the complete destruction of the military power of the enemy. I have, on other occasions, attempted to show that to yield to his demands and acknowledge his independence, thus resolving the Union at once into two hostile governments, with a certainty of further disintegration, would annihilate the strength and the influence of the country as a member of the family of nations; afford to foreign powers the opportunity and the temptation for humiliating and disastrous interference in our affairs; wrest from the Middle and Western States some of their great natural outlets to the sea and of their most important lines of internal communication; deprive the commerce and navigation of the country of two thirds of our sea-coast and of the fortresses which protect it: not only so, but would enable each individual State, — some of them with a white population equal to a good-sized Northern county, — or rather the dominant party in each State, to cede its territory, its harbors, its fortresses, the mouths of its rivers, to any foreign power. It cannot be that the people of the loyal States — that twenty-two millions of brave and prosperous freemen — will, for the temptation of a brief truce in an eternal border-war, consent to this hideous national suicide…”

“But the hour is coming and now is, when the power of the leaders of the Rebellion to delude and inflame must cease. There is no bitterness on the part of the masses. The people of the South are not going to wage an eternal war for the wretched pretexts by which this rebellion is sought to be justified. The bonds that unite us as one People, — a substantial community of origin, language, belief, and law (the four great ties that hold the societies of men together); common national and political interests; a common history; a common pride in a glorious ancestry; a common interest in this great heritage of blessings; the very geographical features of the country; the mighty rivers that cross the lines of climate, and thus facilitate the interchange of natural and industrial products, while the wonder-working arm of the engineer has levelled the mountain-walls which separate the East and West, compelling your own Alleghanies, my Maryland and Pennsylvania friends, to open wide their everlasting doors to the chariot-wheels of traffic and travel, - these bonds of union are of perennial force and energy, while the causes of alienation are imaginary, factitious, and transient. The heart of the People, North and South, is for the Union...

“And now, friends, fellow-citizens of Gettysburg and Pennsylvania, and you from remoter States, let me again, as we part, invoke your benediction on these honored graves. You feel, though the occasion is mournful, that it is good to be here. You feel that it was greatly auspicious for the cause of the country, that the men of the East and the men of the West, the men of nineteen sister States, stood side by side, on the perilous ridges of the battle. You now feel it a new bond of union, that they shall lie side by side, till a clarion, louder than that which marshalled them to the combat, shall awake their slumbers. God bless the Union; — it is dearer to us for the blood of brave men which has been shed in its defence. The spots on which they stood and fell; these pleasant heights; the fertile plain beneath them; the thriving village whose streets so lately rang with the strange din of war; the fields beyond the ridge, where the noble Reynolds held the advancing foe at bay, and, while he gave up his own life, assured by his forethought and self-sacrifice the triumph of the two succeeding days; the little streams which wind through the hills, on whose banks in after-times the wondering ploughman will turn up, with the rude weapons of savage warfare, the fearful missiles of modern artillery; Seminary Ridge, the Peach-Orchard, Cemetery, Culp, and Wolf Hill, Round Top, Little Round Top, humble names, henceforward dear and famous, — no lapse of time, no distance of space, shall cause you to be forgotten.

“‘The whole earth,’ said Pericles, as he stood over the remains of his fellow-citizens, who had fallen in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, — “the whole earth is the sepulchre of illustrious men.” All time, he might have added, is the millennium of their glory. Surely I would do no injustice to the other noble achievements of the war, which have reflected such honor on both arms of the service, and have entitled the armies and the navy of the United States, their officers and men, to the warmest thanks and the richest rewards which a grateful people can pay. But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country there will be no brighter page than that which relates THE BATTLES OF GETTYSBURG.”

Topics: