February 6, 2019

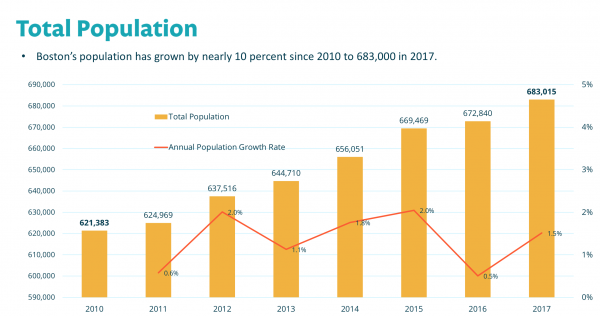

A BPDA graphic shows the population boom and its rate of growth since 2010.

While Boston’s population continued to grow and become more diverse in the first seven years of the 2010s decade, the city grew more expensive to live in, according to Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) demographic trend reports.

One overview January report, pulled together by the department’s research division from American Community Survey data, reviews demographics from 2010 to 2017 in Boston proper. A more in-depth report, Boston in Context, breaks the 2017 snapshot down by city neighborhood boundaries.

During that time, Boston’s population boomed. From some 622,000 people in 2010, the city grew by 10 percent to 683,000 residents in 2017. Dorchester remains the largest neighborhood by a wide margin at 125,947, although differences between locally and city-defined boundaries mean the population is likely higher. No other neighborhood has more than 53,000 residents.

The growth, while trending upward, was not always steady. In the years 2012 and 2015, population jumped 2 percent over the prior years, while 2016 saw only half a percent in growth. Then between 2016 and 2017, it rebounded on a plus swing, up 1.5 percent and counting about 11,000 new Bostonians over the year before.

“As the population has grown, the median age increased by 1.5 years to 32.3 years,” the BPDA report states. That marks a roughly 5 percent increase in the average age over the seven-year stretch. Aside from the small Harbor Islands population, West Roxbury has the highest median age in 2017: 43 years. Dorchester and Mattapan fall in the middle of the pack, at 33 and 37 years, respectively.

Geographic mobility declined at the same time. The share of the population remaining in the same house as the prior year increased to 79.5 percent, those changing houses within Suffolk County fell to 9 percent, and people moving to Boston from outside Massachusetts fell to 4.1 percent.

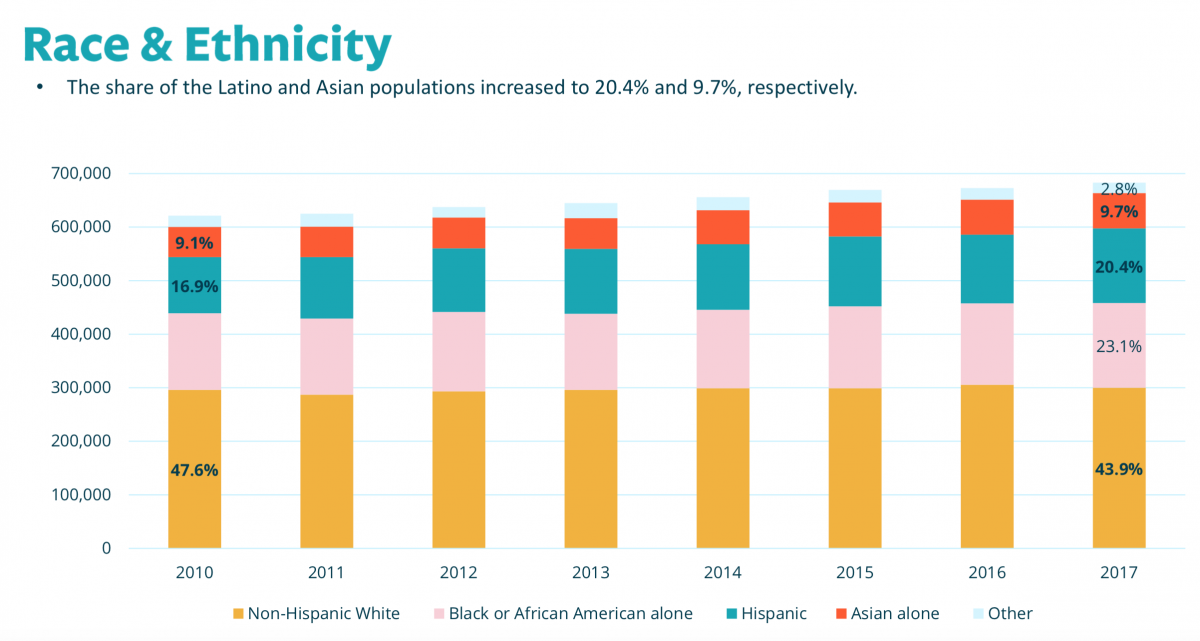

Boston remains a majority-minority city, with white residents making up about 44 percent of the population compared to 47.6 percent in 2010. The share of the population composed of Latino and Asian residents increased to 20.4 percent and 9.7 percent, respectively, and the share of black residents remained relatively steady at 23 percent.

The least diverse neighborhoods are Beacon Hill, the North End, and the South Boston Waterfront, all more than 80 percent white, with the waterfront only 2.7 percent black. Mattapan is nearly the reverse, with 73 percent of its population identifying as black and only 7 percent white. Dorchester is more of a mixture — about 21 percent white, 45 percent black, 18 percent Hispanic/Latino, and 9 percent Asian.

Dorchester also has the most foreign born residents — 43,261 — a full 40 percent hailing from the Caribbean but also a robust 23 percent from Asia and 21 percent from Africa. About 84 percent of Mattapan’s 8,404 foreign-born residents are from the Caribbean.

“Boston became increasingly populated by foreign-born residents,” the report said, up to 29.3 percent of the city in 2017 from 26.9 in 2010. Although, researchers found, “there was no significant change in the regions of the world from which immigrants came to Boston.”

It follows, logically, that the share of the population speaking only English at home dropped by about 3 percent as well. Those speaking a language other than English at home increased to 38.5 percent of residents.

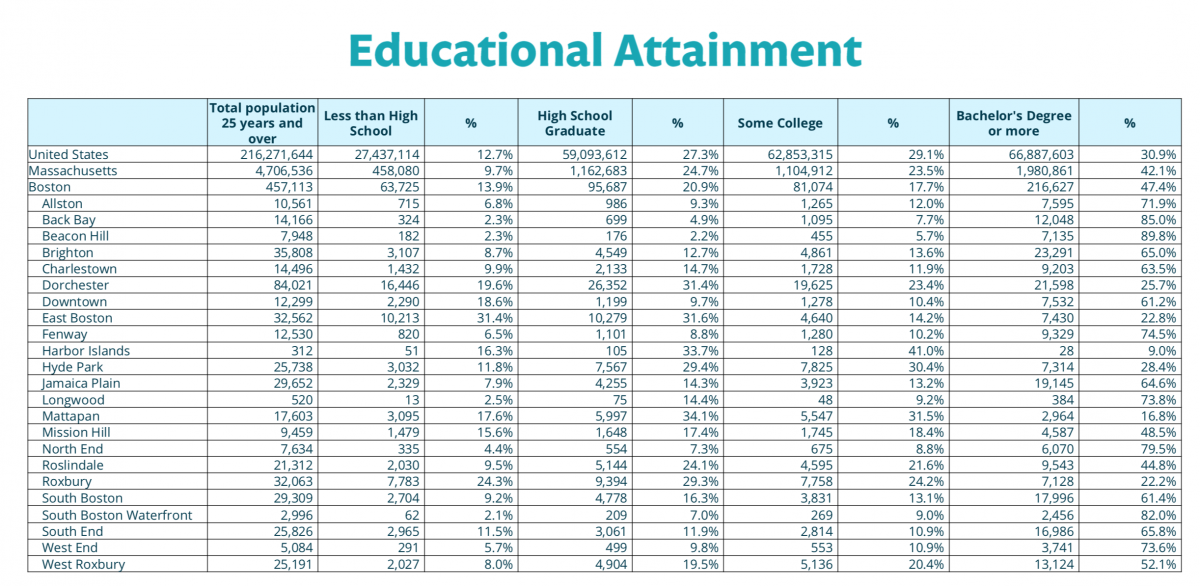

Boston’s reputation as a highly educated city holds true as a whole in the recent report. Just over 22 percent of residents over 25 had a graduate or a professional degree in 2017, about 2 percent more than in 2010. They are included in the 47 percent of residents that had at least an undergraduate degree across the study period.

Disparities exist by neighborhood. Just under a quarter of Roxbury residents have less than a high school education, almost twice the city average. About 31 percent of East Bostonians also do not have a high school education.

Mattapan, Roxbury, Dorchester, and Hyde Park had the lowest percentages of those with bachelor’s degrees or higher — 17, 22, 26, and 28 percent, respectively — while the rest of the city sat mostly in the 60 to 80 percent ranges.

Management, business, science, and arts occupations spiked over the seven years, rising to more than half of the workforce by 2017. Sales and office occupations slumped slightly, dropping 3 percent to make up about 19 percent of the workforce.

“The share of residents age 16 or older who participate in the labor force remained unchanged at about 69 percent,” the overview report said.

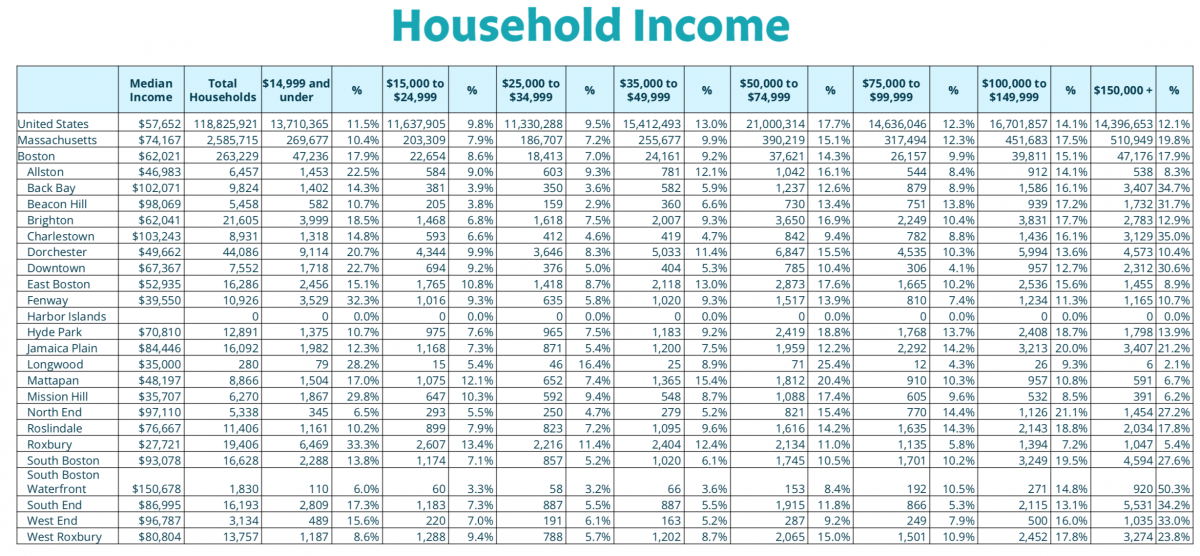

Wages also rose. Each income bracket’s mean household income increased by at least 17 percent, adjusted for inflation. The fifth of the population making the least — under $18,083 annually — saw the largest percentage gain in mean household income: 29 percent growth to $8,986. The top income bracket rose from a $237,355 mean annual income to $283,180.

Neighborhoods with more populations of color or higher college student density made the lowest per capita income, with Roxbury’s only $18,932 and Dorchester’s at $26,292 in a city with a 2017 average of almost $37,000. Those in the Seaport, Beacon Hill, and Back Bay made per capita incomes of more than $90,000.

Poverty rates on the whole have declined, the overview report found, and “the share of residents living below the poverty threshold decreased to 18.7.” That accounts mostly for Dorchester and Roxbury, which house 23.3 percent and 13 percent of the city’s impoverished population, respectively.

Upshots in education and income crash up against similar increases in living and housing costs. Since 2010, about 15,000 units of housing were built in Boston, with a fairly stable occupancy rate of around 91 percent. The lowest rate of occupancy is Downtown, just below 80 percent, while Dorchester and Mattapan both sit at 92 percent occupancy. Owner-occupied units increased to 35.2 percent of all units, plummeting in college-heavy areas like Allston (9.8 percent) and Mission Hill (9.4 percent). Dorchester and Mattapan fall at just about the city average, though Roxbury is only 20 percent owner-occupied.

The average monthly rent rose during the period from $1,386 to $1,541.

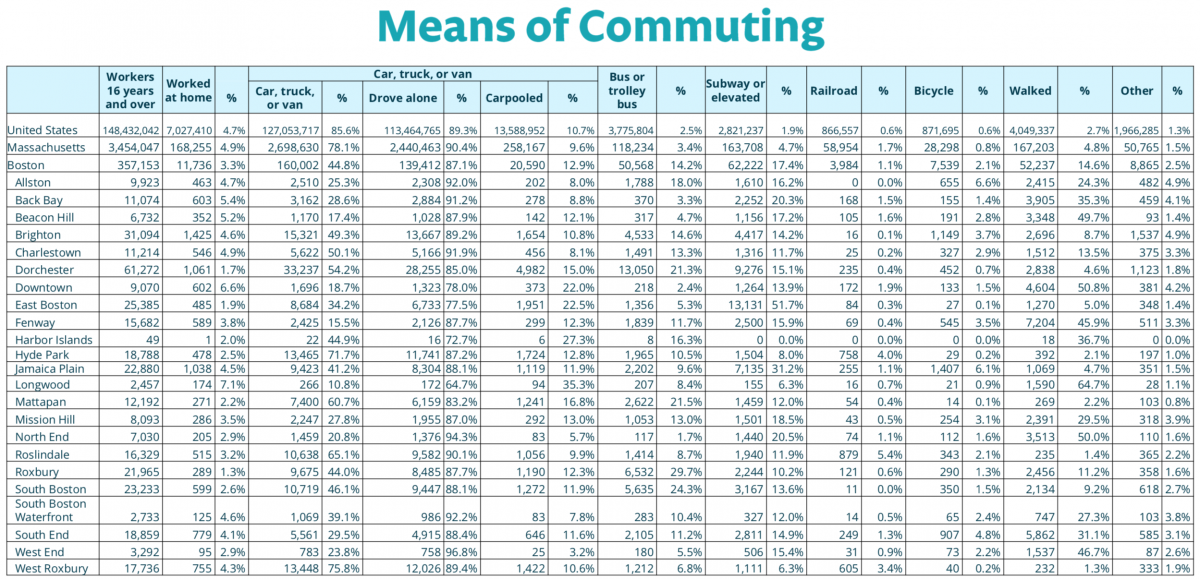

The last section of the reports tackled transit. “There was little change in commute mode from 2010 to 2017,” the overview report said.

About 35 percent of the city uses public transit to get to work, 37 percent drive alone, around 6 percent carpool, and those commuting by taxicab, motorcycle, bicycle, or other means doubled since 2017, to 4.2 percent.

Dorchester relies on the Red Line train, the Fairmount Line of the Commuter Rail, parts of the Mattapan Trolley, and a host of buses to serve its population. Commuters in Dorchester travel to work by car 54 percent, by bus or trolley 21 percent, subway or elevated rail 15 percent, by railroad 0.4 percent, by biking 0.7 percent, and by walking 4.6 percent.

The full reports can be found at bostonplans.org/research/research-publications.

Jennifer Smith can be reached at jennifer.smith@dotnews.com, or follow her on Twitter at @JennDotSmith