February 14, 2019

To the casual observer, Sergeant Brian Dunford’s current line of work with the C-11 police district’s Community Service unit might seem predestined. Dunford, at left, was born with blue blood: his father, Robert, helmed C-11 for over a decade and ended his career as Boston Police superintendent. But despite strong family ties, joining the police force was not Brian’s first career choice.

“I actually wanted to be a writer in college,” Dunford told the Reporter last week as he sipped a coffee at Homestead cafe in Fields Corner. “But I got out and couldn’t really get a writing career off the ground.”

The Dorchester native said he landed on police work after quitting a series of small jobs and realizing he wanted to “do something I could be proud of, and be passionate about.” He spent several years in Roxbury, East Boston, and South Boston as a patrol officer and a detective before joining C-11 in 2017. After doggedly keeping his literary aspirations alive through that period, Dunford has a new title as of last month: published author.

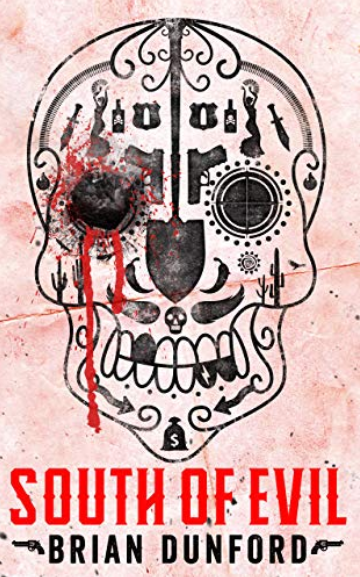

Dunford’s first novel, South of Evil, centers on a forensic accountant in Texas who enlists his buddy, a Boston cop, to help him hunt for a stash of drug cartel money buried in the Mexican desert. Dunford says the idea for the book came to him as he worked a police detail in his cruiser one night in 2010.

“I had a vision of a man dragging a fortune of money through the desert, and I built it from there,” he explained. “[Police] details can be a little boring, and so I occupied myself by building a story in my head.”

The world in Dunford’s novel, one rife with burning vehicles and gory kidnappings, doesn’t exactly mirror his day-to-day life with the BPD.

“Most of it is imagination,” said Dunford. “Most of the characters have serious moral flaws and make terrible decisions — which are much more interesting to me than characters who make good decisions.”

But Dunford added that the narrative is “grounded in reality,” and that for some aspects of the story, he was able to draw on his experiences in law enforcement, a background he views as an advantage from a writing standpoint.

“Most writers who are writing crime thrillers and such aren’t--they haven’t actually seen the things they’re writing about up close and personal, and, unfortunately, I have.”

Writing from the perspective of both the cop and the criminal, Dunford would often take out his laptop in the little free time he had before and after shifts, crafting the novel in close proximity to his police work.

“I wrote most of this while I was a detective, and I loved being a detective. So, I love to think some of that is on the page.”

Dunford’s fictitious setting south of the border certainly does not reflect the state of things in his home precinct of C-11, where (here Dunford rapped his knuckles on the table) the police have yet to respond to a homicide in 2019.

“This neighborhood is ready to pop,” he said, pointing out the window towards the corner of Dorchester Avenue and Adams Street. “When Dot Block moves in down the street, I think there’s going be a lot more business, and a lot more customers are going come down here.”

That optimism is in large part due to recent trends that indicate violence in the neighborhood is on a downward trajectory.

“Here’s where we are: violent crime, part one crime is way down,” Dunford began, taking stock of his district. “It’s been going down consistently for years...Homicides, in 2017 when I first arrived, we had 16 of them. In 2018 we had seven. Those numbers, I think, are phenomenal. I’m not trying to jinx us, but this year, so far, we’ve had none. City-wide, I think we had 57 fewer shootings, which is enormous. The fact that homicides kept up at the rate they did, I can’t explain it. Maybe we’ll look back in future years and see a trend that we didn’t realize was happening.”

But where part one crimes have dwindled, nonviolent crimes have spiked, Dunford acknowledged.

“What we are seeing an increase in is small larcenies, and it’s being driven by drugs and homelessness, which are two things that have hit the entire city of Boston all at once,” he said.

Dunford pointed to the 2015 closure of Long Island, which housed the city’s largest homeless shelter and detox center, as the primary cause of those trends.

“There’s 700 beds or something on that island, and now it’s all here,” he reasoned. “People from here call us with legitimate frustrations, and I feel bad for them, but a jail cell is not the place for a homeless person. It’s not the place for someone who’s detoxing from drugs. Nothing good is going to come from it.”

Interacting with and helping out the homeless has become a considerable part of Dunford’s job since joining Community Service, and the BPD’s new model of “community policing” means his unit has adopted more creative, less traditional approaches to getting citizens the resources they need.

“There’s lots of good agencies that already exist, it’s just a matter of partnering with them,” he said. “We have a direct hotline to Bay Cove or Pine Street Inn. We have a homeless outreach coordinator at Boston Police, that’s what he does. So instead of using like a 1970s model of going out there and yelling at a guy to ‘Hey, don’t come back again or you’re getting arrested,’ we actually go up there with resources and offer the guy help.”

Another issue community policing efforts have tackled is gang involvement, by way of getting to kids earlier and building relationships based on mutual trust rather than fear.

“One place we’ve realized kids are already there is the St. Peter’s Teen Center [on Bowdoin Street]. So, we’ve been doing a lot of work with them...you get up there and you meet them when they’re younger and they don’t have that ingrained fear of the police--they go, ‘Oh, I know that guy.’”

One of the unit’s successes that Dunford touted is a “boot camp” that C-11 officials host at the teen center, which he described as “a military-style workout” featuring pushups, situ-ps and calisthenics. The boot camp also includes a series of no-contact boxing drills, which Dunford says has resonated most closely with the teenage girls in the program.

“You can tell some of the kids really take to it, and you look around the room going, ‘Future Marine, future Marine.’ But also, when we’re up there we say, ‘Hey guys, we’re hiring cadets in a few months. If you guys are 16-17 years old, let’s take the test and get you guys in the pipeline. These are the kids we’re looking for.”

Dunford’s anecdotes from Community Service may very well serve as the basis of his next novel. The feedback for South of Evil he’s received so far has been “better than [his] wildest dreams,” and has already encouraged him to publish another book in the future. He noted that most readers have reacted positively to the “twists and turns” that characterize the plot line.

“I went to great lengths to make sure that every character changes at some point, and develops into something new, in that there are surprises throughout the book,” he explained. “In the first round of reviews I’m getting, people are raving about the ending.”

South of Evil is available for purchase in paperback and digital formats on amazon.com and through Kindle Unlimited.