March 26, 2020

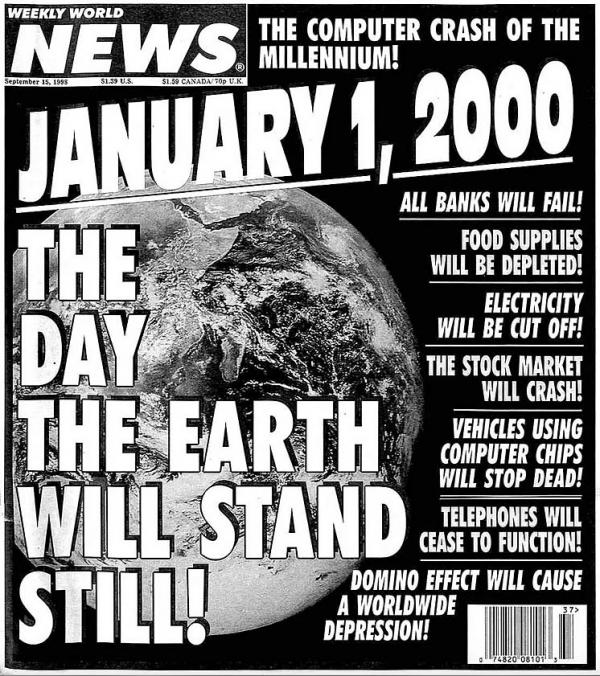

This front page left little doubt as to where the editors stood on Y2K.

A time like this, with all its negative implications, offers a bit of relief to those in what has been called a subset of Americans – book readers. With the guidance from on high that we should stay home as a general rule, there is the opportunity for them to pick up a hard-cover or a paperback or a Kindle or to click on Google and turn away from this time and place to a consideration of other times when such a crisis, or presumed crisis, dominated the news across the world.

For most of 1999, the general media were transfixed by the term “Y2K,” which when followed by the word “crisis,” was shorthand for the idea that all the world’s computers might crash or do other strange things at the stroke of midnight on Dec. 31, 1999, because 30 years before, people building the internet decided not to use four numbers when citing the century in dates; they used just two, as in 02/12/99, instead of 1999, because that saved significant storage space. The fear was that the switch to 2000 would give computers 01/01/00 to deal with, and all working computers might see this as a nullity and crash or shut down, setting off worldwide chaos.

I was the managing editor for news operations at The Boston Globe at the time. To call up our daily editions online, especially those published in the late months up to the very last day of 1999, is to know that the newspaper took the matter very front-page seriously, as did discrete sections of the government, the media, business, technology, and the public. Some thought the world as we knew it would soon be over, others thought that the preparations that had been made in the preceding months would, with all hands on deck at every company that used computers, prevent any type of catastrophe from happening, and, of course, still others spread conspiracies of foreign intervention or just cried “hoax.”

Then the clock struck midnight, and moved on to 12:01 a.m. Jan. 1, 2000, and so did the world.

While there was the usual Monday-morning quarterbacking for days after, most people seemed to feel that the preparation was worth the time, effort, and cost, which was put at several hundred billion worldwide at the time. A problem that could have been terribly damaging had been recognized as such early on and prepared for directly and publically to the best of society’s abilities.

Bill Bryson, in his book “The Body,” which was published last year:

“Every February, The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control get together and decide what to make the next flu vaccine from, usually based on what’s going on in eastern Asia. The problem is that flu strains are extremely variable and really hard to predict. …

“Based on all the available information, the WHO and CDC announce their decision on Feb. 28, and all the flu vaccine manufacturers in the world begin working on the same strain. Says [Dr. Michael] Kinch [of St. Louis], “From February to October, they make the new flu vaccine in the hope that we will be ready for the next big flu season. But when a really devastating new flu emerges, there’s no guarantee we will actually have targeted the right virus.”

While the two agencies did their jobs and did target the anticipated flu strain appropriately for new vaccine purposes, something was happening in 2019, China that would upend that accomplishment and startle the world’s public, if not its national intelligence agencies, as the new year began.

John M. Barry, on the 1918-1920 “Spanish flu” catastrophe in the November 2017 edition of Smithsonian Magazine:

“Wherever it began, the pandemic lasted just 15 months but was the deadliest disease outbreak in human history, killing between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide, according to the most widely cited analysis.

“The impact of the pandemic on the United States is sobering to contemplate: Some 670,000 Americans died. …

“The killing created its own horrors. … What proved even more deadly was the government policy toward the truth. When the United States entered the war, President Woodrow Wilson demanded that “the spirit of ruthless brutality...enter into the very fibre of national life.” So he created the Committee on Public Information, which was inspired by an adviser who wrote, “Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms. ... The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it is true or false.”

“At Wilson’s urging, Congress passed the Sedition Act, making it punishable with 20 years in prison to “utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United State...or to urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of production in this country of anything or things...necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war.” Government posters and advertisements urged people to report to the Justice Department anyone “who spreads pessimistic stories...cries for peace or belittles our effort to win the war.”

Against this background, while influenza bled into American life, public health officials, determined to keep morale up, began to lie.”

History will eventually confirm the effects, deleterious or not, of President Donald Trump’s rhetorical vacillations and back-and-forth public actions as COVID-19 spread across the country in late winter into the spring this year just as history, in the person of one historian/philosopher, confirmed, in writing about the Pentagon Papers, what hiding the truth did 50-plus years ago as the war in Vietnam tore the country asunder.

Hannah Arendt, “Lying in Politics,” excerpted from the Nov. 18, 1971, edition of the New York Review of Books:

“When we talk about lying, and especially about lying among acting men, let us remember that the lie did not creep into politics by some accident of human sinfulness; moral outrage, for this reason alone, is not likely to make it disappear. The deliberate falsehood deals with contingent facts, that is, with matters which carry no inherent truth within themselves, no necessity to be as they are; factual truths are never compellingly true. The historian knows how vulnerable is the whole texture of facts in which we spend our daily lives; it is always in danger of being perforated by single lies or torn to shreds by the organized lying of groups, nations, or classes, or denied and distorted, often carefully covered up by reams of falsehoods or simply allowed to fall into oblivion. Facts need testimony to be remembered and trustworthy witnesses to be established in order to find a secure dwelling place in the domain of human affairs. From this, it follows that no factual statement can ever be beyond doubt—as secure and shielded against attack as, for instance, the statement that two and two make four.…

Under normal circumstances the liar is defeated by reality, for which there is no substitute; no matter how large the tissue of falsehood that an experienced liar has to offer, it will never be large enough, even if he enlists the help of computers, to cover the immensity of factuality. The liar, who may get away with any number of single falsehoods, will find it impossible to get away with lying on principle. This is one of the lessons that could be learned from the totalitarian experiments and the totalitarian rulers’ frightening confidence in the power of lying—in their ability, for instance, to rewrite history again and again to adapt the past to the “political line” of the present moment, or to eliminate data that did not fit their ideology, such as unemployment in a socialist economy, simply by denying their existence: the unemployed person becoming a non-person.

The results of such experiments when undertaken by those in possession of the means of violence are terrible enough, but lasting deception is not among them. There always comes the point beyond which lying becomes counterproductive. This point is reached when the audience to which the lies are addressed is forced to disregard altogether the distinguishing line between truth and falsehood in order to be able to survive. Truth or falsehood—it does not matter which any more, if your life depends on your acting as though you trusted; truth that can be relied on disappears from public life and with it the chief stabilizing factor in the ever-changing affairs of men.”