May 13, 2021

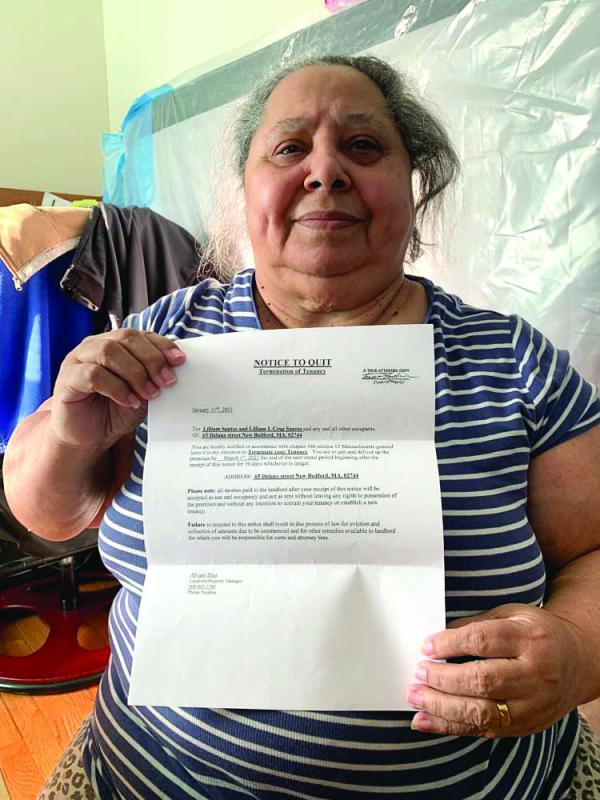

New Bedford resident Liliana Cruz holds up a copy of the eviction letter she received in January. The landlord wants her out by the end of May. Simón Rios/WBUR

Liliana Cruz choked up at her kitchen table in New Bedford as she talked about faithfully paying her rent — every month over the last five years. Despite that, her landlord has sent her a notice ordering her to leave the three-bedroom house by the end of this month.

“From one day to the next, it doesn’t matter what I pay, I have to go,” she said in Spanish. “And I don’t bother the landlord with anything. I spent my own money to fix the bathrooms. This is heavy, but God gives me strength.”

The number of evictions filed in Massachusetts courts is slowly returning to the level it was before the pandemic. That’s despite a federal moratorium on evictions, and hundreds of millions in federal dollars to help Massachusetts renters stay in their homes.

Landlords filed more than 1,500 eviction cases against Massachusetts renters in April alone, about half the number of evictions filed in the same month two years ago, before the pandemic began.

Joe Kriesberg is head of the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations, a group of agencies that provide affordable housing and local services. He said the situation would have been far worse without the flood of state and federal aid to help people deal with the pandemic.

“The combination of measures that have been implemented over the last 14 months, the moratorium ... the mediation, the legal services, the rent relief dollars, all told, has helped prevent thousands and thousands of evictions. We went months with essentially no formal evictions,” Kriesberg said.

But the state evictions ban ended in October. And the federal moratorium from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is weaker. Instead of banning evictions outright, it only bars them in certain circumstances. And not everyone qualifies or knows how to use the rule. While the state moratorium covered all kinds of evictions, the CDC moratorium is aimed more narrowly at nonpayment evictions, said Steve Meacham of the housing rights group City Life/Vida Urbana.

“And, so, there’s a lot of people who move when they get the notice to quit that before they ever even go to court,” Meacham said.

But even that more limited protection is set to expire at the end of June, and Meacham fears that could lead to a new surge in evictions.

[On May 5, a federal judge in Washington ruled that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had overstepped its legal authority by issuing a nationwide eviction moratorium, a ruling that could affect millions of struggling Americans.

[In a 20-page order, US District Judge Dabney Friedrich vacated the CDC order, first put in place during the coronavirus pandemic under the Trump administration and now set to expire June 30. The Biden administration has suggested it will appeal the judge’s ruling.]

Unless the CDC moratorium is extended, the state’s eviction prevention program could be a last resort for some renters.

Massachusetts is currently sitting on roughly $968 million in relief money, state officials say, mostly from the federal stimulus money designed to curb the pandemic. Since the pandemic hit, the state has spent less than $200 million of that amount. It has served roughly 25,000 households.

But Doug Quatrocchi of Mass Landlords says the program leaves out more people than it helps. He points to state data that show 57 percent of applications for rent relief have been rejected, either because people didn’t qualify or because of incomplete applications.

Quatrocchi thinks that’s because the state’s requirements are too stringent.

“It’s the age-old conflict where on the one hand, we want to help people, but on the other hand, we’re so twisted up in knots about potential fraud and helping any one person who doesn’t deserve it,” he said. “But in the end, we’re not helping the majority of people who deserve it.”

The state said applications were closed primarily because the requests for aid were incomplete or because it couldn’t secure full cooperation from both the tenant and the landlord.

State housing officials say the state’s largest eviction diversion initiative — Residential Assistance for Families in Transition — or RAFT — has been streamlined since the pandemic began. And they want people to know that money is available. Now the state is working with local groups to get the word out, such as the Coalition for Social Justice in New Bedford.

The coalition’s Dax Crocker pulled up a smartphone app with a map of the city to guide him. After a few seconds, his screen filled up with tiny icons of houses, each one representing someone facing eviction in housing court.

He knocked on a door, but nobody answered. It’s the third straight place he has visited with no one home.

But even if someone opens the door, it’s not clear whether the RAFT program could help. Sometimes it’s because of the landlords.

“I have had people ... who have literally told me that the reason why the landlord wants them out is because they want somebody else who can pay more rent ... so they don’t cooperate with RAFT,” Crocker said.

How often does he see RAFT working?

“Twenty-five percent of the time, maybe, not a lot,” he said.

Crocker’s fourth visit that day was to the woman whose landlord wants her out at the end of this month, Liliana Cruz.

But RAFT couldn’t help Cruz, either. That’s because she already has just enough money to pay the rent. The problem is her landlord wants the apartment back, and RAFT isn’t designed to help people like her.

Cruz said finding a new place she can afford isn’t easy. Every apartment she looks at charges an application fee that she can’t afford. And everybody involved speaks English, which she doesn’t understand.

Now Cruz feels her only hope is that the federal moratorium will allow her to keep her home a while longer.

“This is your house,” she told her visitors. “As long as I’m still here.”