April 6, 2022

Melvin Vieira, Jr., president of the Greater Boston Board of Realtors: “Have I seen my clients who are African American or Latino, Asian or whatever, have I seen them jump through more hurdles? Get more paperwork? Yes, I have.”

First in a three-part series

Owning a home is considered part of the so-called American dream, but for Black and Hispanic Bostonians, it is more often a dream denied.

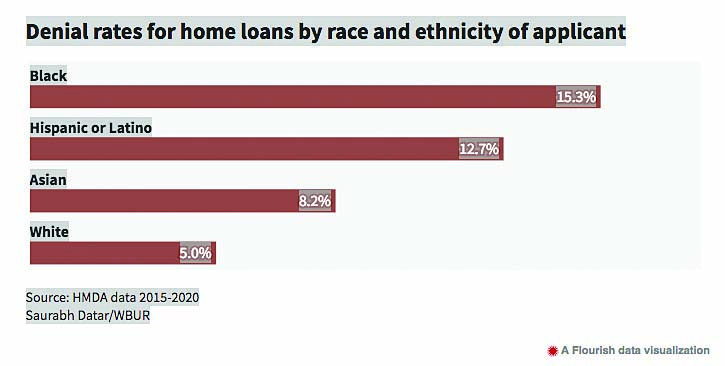

A new WBUR analysis of mortgage lending in Boston from 2015-2020 found that lenders denied mortgages to Black applicants at three times the rate of white applicants. Hispanic applicants were twice as likely to be denied a loan compared with white applicants.

Manny Bello knows that disappointment well. Last spring, he found a great single-family house in Mattapan. It had enough space for him, his wife, and their three kids, and a finished basement where he could put a home office. It also had a large garage and driveway that would be perfect for the vehicles from his cleaning business.

“I thought I had hit the jackpot,” said the 46-year-old Bello, who identifies as Hispanic. “It was the perfect fit. And I was just in love with the house.”

It took Bello eight years to get to this point. He spent that time saving money and preparing for homeownership. He worked his way up to become a manager at a janitorial company. And he started his own cleaning business on the side, which increased his income. He also built up his credit score, getting it to the 800s — the highest range. He was ready.

“The loan officer told me that I have the perfect package,” he said.

He went through a loan pre-approval process. He had a closing date. And his kids were even picking out their rooms. “And then I got denied at the last minute,” Bello said. “It was heartbreaking.”

Bello said the mortgage underwriter told him he was denied because his cleaning business was a few months short of two years old, so that income wouldn’t be considered for the application. In other words, the lender would only factor in one of his streams of income, which wasn’t enough to get the loan he needed for the home in Mattapan.

“I was very disappointed,” Bello said. “I just said, ‘You know, if this is the reason and there’s nothing I can do, well, thank you very much, and I guess I’ll just stop looking for a property right now.’”

So, Bello has put homeownership on pause. He isn’t sure when he’ll try again.

“I don’t want to go through the process again and be denied at the last minute,” he said.

WBUR’s analysis of publicly available federal data through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) found that 3,501 applications for loans to purchase homes were denied in Boston between 2015 and 2020, amounting to 6 percent of all such applications.

In addition to the higher denial rates for Hispanic homebuyers, the numbers were working against Bello in another way: It’s harder to secure home loans for properties in predominantly Black parts of the city, like where he was looking in Mattapan. WBUR found that lenders denied loans for home purchases in majority-Black parts of Boston at 2.5 times the rate of majority-white areas.

Homeownership isn’t just about fulfilling a dream. It’s the primary way most Americans build wealth. So, when Black and Hispanic residents encounter more hurdles when trying to finance a home purchase, the ramifications are broad and lasting.

“Homeownership is one of the major drivers in the racial wealth gap,” said Tatjana Meschede, associate director of the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity at Brandeis University.

An often cited study by the Boston Fed in 2015 found the median net worth of a white household in Greater Boston was approximately $250,000, while the median figure for a non-immigrant Black household was $8.

Lending industry representatives say the data WBUR used in its analysis doesn’t tell the full story about denial rates. They attribute the higher denial rates for Black and Hispanic borrowers to differences in credit scores, debt, or loan size relative to the value of the home.

“We believe the HMDA data that underlies your story can help identify potential lending disparities within the mortgage market but given limitations with the data, the numbers are not sufficient on their own to explain why those disparities exist,” Blair Bernstein, director of public relations for the American Bankers Association, told WBUR in a statement.

Some of the data that lenders say explains the gap, such as credit scores, are not made public, but are available to regulators. Last year Federal Reserve researchers found that factors such as credit scores, property values, income and mortgage loan algorithms explain most of the racial gap in denial rates, but not entirely, “suggesting a possible role for discrimination.” And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau analyzed 2019 HMDA data and found that disparities weren’t eliminated when factoring in credit scores.

Locally, a report released in August by the Massachusetts Community Banking Council found that Black and Hispanic loan applicants were more likely to be denied even when adjusting for the borrower’s income, debt, and other factors.

“Even high-income Black borrowers are less likely to receive a loan or are more likely to be denied a loan than their white counterparts,” said Sarah Philbrick, a research analyst formerly with the Metropolitan Area Planning Council. In 2017, the agency studied denial rates among high-income loan applicants in metro Boston.

The challenges many people of color face today in trying to buy a home — and secure the financing to do so — reflect history. Experts say racial disparities in mortgage lending can be traced to the same thing: structural racism.

“The lending patterns today and the disparities that we see today are basically reproducing the patterns that have been here for quite a while,” said Jim Campen, a professor emeritus at University of Massachusetts Boston who has studied mortgage lending in the city.

There is a long history of racial discrimination in housing. Under the federal policy that became known as redlining, banks refused to lend in Black and immigrant neighborhoods in cities like Boston from the 1930s through the 1960s. Additionally, racially restrictive covenants — contracts embedded in property deeds — were used to ban people of color from living in white neighborhoods.

“The historical policies we had in this country just didn’t provide the same opportunities for Black households compared to whites,” said Meschede, of Brandeis University.

As a result, Black borrowers often have lower incomes, less money saved, and less ability to get financial help from their families than white borrowers — and therefore are less able to afford homes and acquire loans. Past discrimination is baked into the current mortgage lending gap, experts say.

“When you look at that mortgage transaction, you’re really at the end of a long string of other factors that discriminate against people of color that have created obstacles to owning homes as well,” said Chris Herbert, managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University.

In Boston, the homeownership rate for white residents is 44 percent, while it’s 30 percent for Black residents and 17 percent for Hispanic residents. City data show that the gap has actually widened since Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968, which made redlining illegal.

And studies since then provide strong evidence that discrimination has continued.

Says Chris Herbert: “When you look at that mortgage transaction, you’re really at the end of a long string of other factors that discriminate against people of color ...”

The Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston conducted an investigation in 2006 in which volunteers of different races applied for loans at the same banks. The center, which has since closed, found that loan officers often gave white applicants more loan options and discounts on closing costs — even when Black, Hispanic and Asian applicants were better qualified. Overall, the study found evidence of discrimination in half the cases.

Melvin Vieira, Jr., president of the Greater Boston Board of Realtors, said some of his clients have been treated differently when they tried to get a mortgage loan.

“Have I seen my clients who are African American or Latino, Asian or whatever, jump through more hurdles? Get more paperwork? Yes, I have.”

This is what lending discrimination looks like now, some housing experts say. It’s more subtle and often harder to spot.

And it’s not just individual loan officers’ behavior. Company decisions, like where to open up branches or whom to market to, can also lead to discrimination.

The US Justice Department has found that some banks have discriminated against Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, and recently announced an initiative to combat “modern-day redlining.”

But even if all traces of lending discrimination were to be erased, Campen said he believes there would still be a homeownership gap. “The racial problems and the problems of inequality in this society are so deep and so long and so severe that we’re not going to end them by tinkering around making changes in the mortgage lending system — as important as that is,” he said, especially, he added, since all of this is happening in the midst of a housing shortage and a market with rising home prices.

“If you want to have greater Black homeownership in the city of Boston, you need to make either homes more affordable or Blacks richer,” Campen said. “Or both.”

This article was originally aired and published by WBUR 90.9FM on March 30. The Reporter and WBUR share content through a media partnership.