November 21, 2023

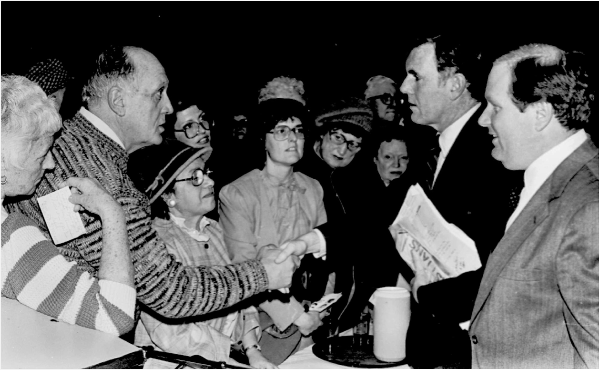

Mayor Ray Flynn is shown after the 1983 election in a Dorchester event with then State Rep. Paul White at his side. Flynn’s successful ’83 campaign included some 125 house parties. In the final election on Nov. 15, 1983, Flynn won Dorchester’s Ward 16 by a 10-1 margin over Mel King. Chris Lovett photo

It was 1983, and the nation was just starting to climb back from double-digit unemployment. More than 2,000 people would die from a newly discovered disease called AIDS. Time Magazine’s Man of the Year was “The Computer,” and Michael Jackson would update the shuffle into the fractured poise of the “moonwalk.”

On the streets of Roxbury and Dorchester, a section of the Caribbean American Carnival would pay tribute to Mohandas K. Gandhi, passing by words from Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, from 20 years earlier, that were displayed outside a church near Grove Hall. Throughout Boston, 1983 was counted by many as nine years after the explosive start of school desegregation and, by some, as twenty years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. In the preceding decade, the city had lost more than 12 percent of its population. And, after 16 years under Mayor Kevin H. White—then the longest mayoral tenure in Boston history – it was time to choose a successor.

In 1975, all members of the City Council and School Committee were white, and one of the main opponents of desegregation, Louise Day Hicks, was a top vote-getter. A few elections later, the ranks of elected officials became more diverse, with voters in 1981 approving the first change in the structure of city government since 1949. Starting in 1983, the council and school committee would each have four members at-large and nine members representing districts, all but assuring racial diversity among elected officials.

Less foreseeable, even during the 1983 campaigns, was how the election would change the character of the city’s leadership. White was a hybrid of urban political machinery and “New Boston” smarts, a former preppie who tempered the Camelot afterglow with rolled-up shirtsleeves.

By his own branding, White was the “loner in love with the city.” Expecting that White would run again, an early front-runner in 1983, former Boston School Committee President David Finnegan, sloganized a choice between “Finnegan or Him Again.” But, when Ray Flynn and Mel King emerged as the two finalists for mayor in October, it was clear that voters wanted a different kind of leader, but also a change from the course toward growth and revitalization that stemmed from the restructuring of 1949.

•••

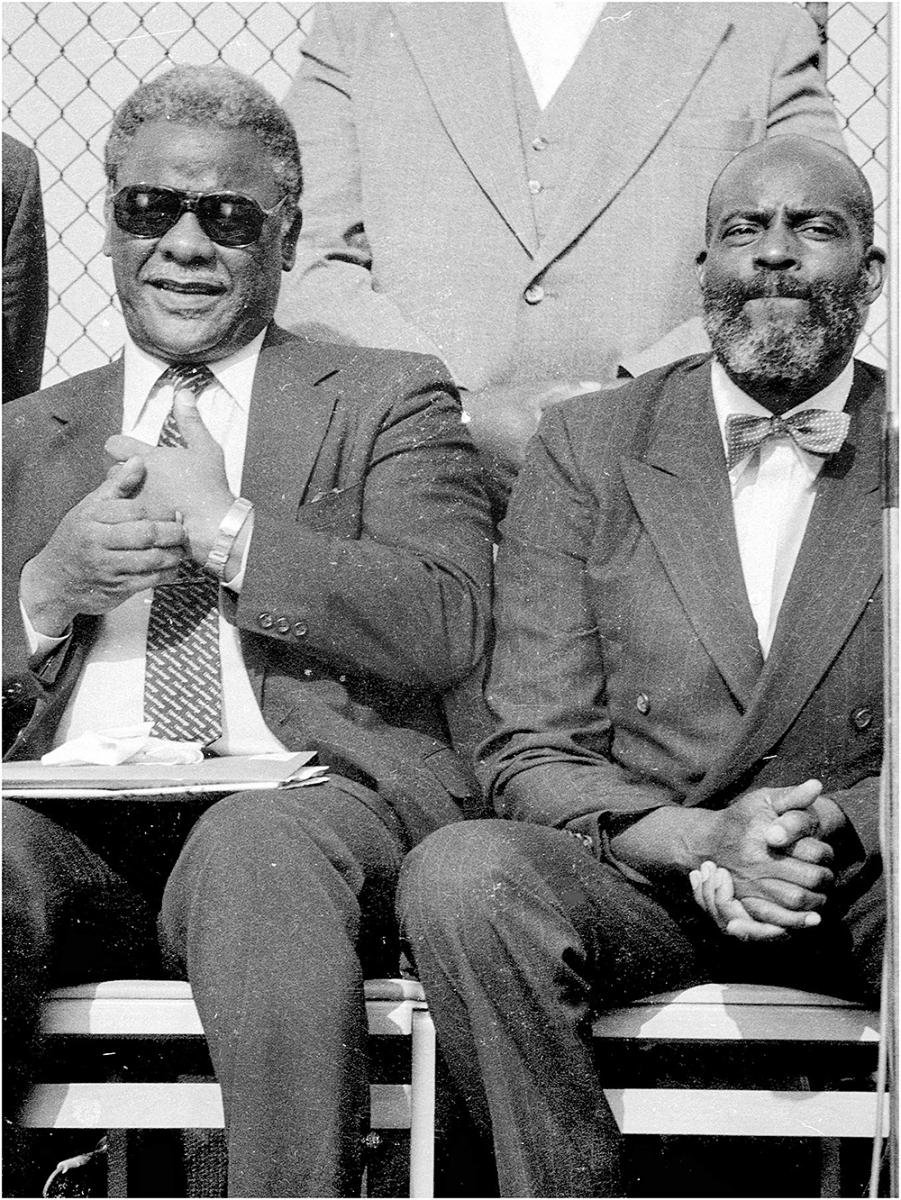

Rep. Mel King, right, was seated next to Chicago Mayor Harold Washington at an August 1983 rally in Grove Hall. Washington was then serving as first Black mayor in Chicago and among the first Black mayors elected anywhere in the United States at the time. Washington told the crowd: “In Chicago, we made it unfashionable to live in the ‘hood and not be registered [to vote].” Mayor Washington served until his death in 1987. Mel King died in March 2023 at age 94. Chris Lovett photo

A former state representative from the South End, King was a refugee from the first Boston neighborhood to be seized by eminent domain and wiped out for urban renewal. By 1983, he had already been a leader in community organizing and electoral politics. A critic of displacement and gentrification, he took part in campaigns for affordable housing and for more diversity in hiring on publicly funded construction projects, which led to the Boston Resident Job Policy. As a legislator, he helped organize the Black Political Caucus, described in his 1981 book, “Chain of Change,” as the Black community’s “real beginning of institution building in the electoral process”

In his book, King denounced Boston’s all-at-large elections as “city imperialism” and a form of “gerrymandering by numbers.” The city’s growing Black population after World War II was up against a lopsided dominance of white officeholders that has been blamed for stiffening political resistance to desegregation at least as far back as the 1960s. King had tried to change the equation by running unsuccessfully for the school committee. In his first run for mayor, in 1979, he worked on voter registration and coalition building, with an eye to the future. Four years later, the change to district representation would provide new incentives for Black voters, and other constituencies drawn to King’s coalition.

“I think the district representation campaign kind of mobilized those neighborhoods, which have always been shut out. They knew through district representation that there was a chance of having a direct voice in the system of voting,” said Pat Walker, who headed the 1981 campaign for the referendum on district representation and served as field director for King’s mayoral campaign in 1983.

“I would liken the embracing of district representation as a cultural shift,” said King’s 1983 campaign manager, Boyce Slayman. “Generationally, political Boston saw they really needed to do something different. The incumbents were all safe. They were all safe seats, so there’s no risk there. But they could not deny the clamor among the black community for representation.”

The son of a union longshoreman from South Boston, Flynn parlayed the basketball skills that made him an All-American at Providence College and got him a tryout with the Boston Celtics. Like King, Flynn won his first election to the office of state representative. Early on, the South Boston legislator stood out as an opponent of busing remedies for desegregation and for co-authoring a state amendment that would ban the use of Medicaid funding for abortions.

After winning a seat as one of nine at-large Boston city councillors in 1977, Flynn turned his attention to other constituencies and other issues, such as rent control, jet noise, homelessness, and having developers of large projects set aside a percentage of money for affordable housing, an idea known as “linkage.” In 1983, Flynn and King both supported “linkage,” while other candidates favored ideas that would demand less from developers. Voters also weighed in by supporting “linkage” in an advisory question on the November ballot.

By 1983, Flynn had enlisted his own team of activists, campaign workers, and other allies who had been advocates for tenants, involved with Boston’s community schools, or with the largest statewide organizing group in the previous decade, Mass. Fair Share. The group had a large chapter in Dorchester, and its overall mission was to organize across racial lines and address common economic concerns.

Among the Fair Share veterans on the Flynn campaign were Alex Bledsoe, later the head of the Office of Neighborhood Services, and Neil Sullivan, Flynn's chief policy advisor for ten years. Flynn's campaign manager was the late Ray Dooley, a veteran activist who had recently managed the successful campaign that elected Brighton socialist Tom Gallagher as state representative. Dooley entered city government as Director of Administrative Services, the most powerful position in city government other than mayor at that time.

With experience in policy and door-to-door organizing, Sullivan described Fair Share’s work as “outcome-oriented political strategy,” ranging from grassroots mobilization to the drama of public confrontation—a cross between town meeting and “agit-prop.” The same tactics could help mobilize voters and make a splash in the media, especially on television. According to Sullivan, the mission behind the tactics suited a candidate who, like King, understood the value of policy and activism as political currency.

“He recognizes people from other worlds who politically have the same attitude,” said Sullivan. “The only way to reconcile these extraordinary racial divisions is to bring people together around issues they share.”

Among the other candidates trying to send a message of unity was former city councillor Larry DiCara, the first-place candidate for that office in 1979, two years before the top spot was captured by Flynn. In 1983, DiCara vowed to become “everybody’s mayor,” announcing his candidacy in every Boston neighborhood. The goal was to stand apart from a “downtown” incumbent who had yet to announce he would not run again. The strategy was as earnest as it was methodical but, as DiCara acknowledged in his book “Turmoil and Transition in Boston,” it was ill-timed.

“My slogan of wanting to be ‘everybody’s mayor’ was not in sync with those residents who wanted their own personal mayor who reflected their views,” he wrote, “and my relentless efforts to show voters I was the most qualified were not responsive to their personal concerns.”

In contrast with 1967, during the last open competition for mayor, Boston voters were more likely to gather impressions of candidates from television. Drawing on an abundance of campaign events and pre-election forums, TV showed the race in ways that were more direct, personalized, and egalitarian. That was epitomized shortly before the preliminary election, when Finnegan and Flynn campaigns were poised to go on the attack.

According to Sullivan, the first salvo was from Finnegan, still the widely perceived frontrunner, who drew attention to Flynn’s anti-busing past and labeled him a “chameleon,” a common label for candidates who switch positions. Sullivan only found out about it when Flynn called and asked him what a chameleon was. Not realizing why Flynn wanted to know, Sullivan said it was “a lizard,” with barely enough time to explain how the reptile changed colors.

A little later, Sullivan’s answer was duly weaponized in a live TV mini-debate between Flynn and Finnegan in front of City Hall. When Finnegan accused Flynn of switching positions, Flynn accused his rival of calling him a “lizard.” And when Flynn denounced Finnegan’s large advantage in campaign contributions as an attempt by special interests to buy City Hall, the attack assumed the color of self-defense.

Some seasoned political observers viewed Flynn’s performance as a meltdown, too emotionally charged for the supposedly “cool” medium of television. Sullivan said that’s what he feared later that night, when he headed to a Flynn campaign fundraiser in East Boston attended by supporters aligned previously with White and Fair Share—the two camps notoriously at odds. They had seen the mini-debate and, when Sullivan arrived, they were pumped up, almost like a triumphant scene from “Rocky, the hit movie. “They’re now like, yeah, beat him, beat him, beat him,” he recalled. “And I said, ‘Jesus, this working-class thing is real!’”

Finnegan had started his 1983 campaign expecting to challenge White, and his slogan was “Finnegan or him again.” By the summer, in pursuit of an open seat, Finnegan appeared more of an insider, between his campaign positions and backing by former supporters of White.

“The chameleon incident helped Flynn,” DiCara wrote, “because it showed many people that Finnegan was Him Again, a replay of the arrogant mayor who had overstayed his welcome, and Flynn somehow came across as the common man.”

The election results also reflected differences in campaign work, with an advantage to King and Flynn. By Sullivan’s count, the Flynn campaign held 125 house parties—many in Finnegan’s adopted high-turnout neighborhood of West Roxbury. King’s campaign relied heavily on voter registration drives and outdoor events, activities that harkened back to the civil rights movement, but also to the spectacle of city politics before the time of TV and radio.

According to Slayman, King’s mobilization of voters was an extension of his coalition building, which encouraged different constituencies to exert power by developing policy and shaping agendas. That extended support beyond the Black community, but it rallied a nucleus of the community to action.

“The Black Political Task Force, other black elected officials said, ‘Look, let’s get behind this guy. Let’s register and vote because we can win this,’” said Slayman. “And that’s kind of what happened. Each constituency believed that he could win, got excited and did massive voter registration, which again, was not accounted for in the formulating of the polling.”

With nine candidates on the ballot and at least three commonly perceived as frontrunners, the preliminary produced two finalists getting less than 30 percent of the vote, a figure that, even before the voting, seemed within reach for King. One event that embodied the sense of possibility was an August rally in Grove Hall, starting with “Black Power” cheers led by WILD disc jockey James A. Williams and a warm-up by activist-comedian Dick Gregory. That set the stage for the arrival of a limousine with King and Harold Washington, recently elected as the first Black mayor of Chicago.

“In Chicago, we made it unfashionable to live in the ‘hood and not be registered,” Washington told a crowd that stretched clear across Washington Street. “So, we can brag about all we did,” he added, “but the people decided it was time for a change, and they went about and did it.”

As Washington gave his stump speech, King was behind him on the platform with two other political figures – City Councillor Bruce Bolling, bound for the new district seat in Roxbury, and Charles Yancey, a favorite for the council district covering parts of Dorchester and Mattapan. Also brought together at the event were the sounds of Gospel music and the steel drums resonating with King’s family roots in the Barbados and Guyana.

Some observers questioned King’s appeal, whether for a lack of magnetism or for not being like the state’s first Black US senator, Ed Brooke. But a woman from Roxbury at the rally said she planned to work for King’s campaign. Just down Blue Hill Avenue, within earshot of the rally, there was also support for King from two newly registered voters, one who had moved to Boston from North Carolina, the other from Alabama.

“It wasn’t till close to the election, those Roxbury campaigns, where we began to get the kind of traditional Black voter to identify with Mel,” said Walker, “because he was different, ethnically and politically. He was much more progressive than the Black politicians before that time.”

According to Walker, the campaign signed up 90,000 voters in the Black community, but also in other parts of the city, a mixed base that would inspire the branding of King’s “Rainbow Coalition.” The results in the preliminary election drew Sullivan’s and DiCara’s admiration. The latter called the turnout for King in the city’s predominantly Black wards “astonishing,” adding, “I found Mel King’s vote fascinating because for the first time in Boston political history, the minority community rallied behind one of their own.”

After running what DiCara called “guerilla campaigns,” the finalists—who had come together years earlier through basketball and later in the Legislature—were near equals in the vote count. Flynn was in front and behind King, the next highest totals were for Finnegan and DiCara.

•••

The results in the final election, on Nov. 15, were quite different, with Flynn the winner by a 2:1 ratio, sweeping the predominantly white areas of Dorchester. In Ward 16 (Neponset), the ratio was 10:1.

There were incidents of racial violence against the King supporters, but the damage was contained, thanks to cooperation between campaigns and direct communication between Walker and Sullivan. More visible was a display of racial difference and common ground with minimal antagonism, even though people in Boston were still divided about efforts to increase penalties for racial discrimination in housing.

In 2016, in the middle of a divisive presidential election, Flynn reflected on the 1983 campaigns in a joint interview with King on BNN News. “That election, and I praise Mel King as much as anybody for helping bring the city together… wasn’t contentious; it wasn’t divisive,” said Flynn. “We fought hard, we were rivals but, at the same time, the city came out of that election much better than it would have ordinarily.”

As mayor, Flynn overlapped with the King agenda by supporting measures for linkage and rent control. To help secure land for new affordable housing in parts of Dorchester and Roxbury, Flynn flipped the urban renewal script by pressuring the Boston Redevelopment Authority board to give power of eminent domain to the community-based nonprofit Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative.

After being placed in receivership under White, the Boston Housing Authority (BHA) returned to city control under Flynn, who appointed a former legislator and tenant activist, Doris Bunte, as administrator. The later move to desegregate public housing required pressure from the federal government and triggered white resistance. But, as Sullivan explained, a repeat of the clash over schools was avoided, thanks in part to aides with the experience and credibility of neighborhood activists.

“The relationships and the ability to organize around those relationships allowed us to accomplish something that seemed unimaginable at the time,” Sullivan said.

“We integrated public housing, and not one single incident during the Boston Public Housing era,” Flynn recalled. “Contrast that to the public schools. The reason why is because there were people like Mel King and there were neighborhood people, there were clergy, there were people that were invested in the neighborhood who believed in the neighborhood, and who believed in each other.”

Several supporters from both 1983 final campaigns would stay active politically, running for office, serving under elected officials, or working for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) on advocacy, service, or community development. As federal funding for cities decreased, NGOs would play a larger role, partly supported by philanthropies, tax write-offs, and resources from banks made available by the Community Reinvestment Act. After working for Flynn, Sullivan became executive director of the Boston Private Industry Council, a nonprofit whose mission included help for dropouts from the Boston Public Schools.

After a run-off between two candidates positioned as progressive, Flynn would be re-elected twice, without strong opposition. Though DiCara acknowledged that Boston had become less receptive to conservative candidates, he viewed the unprecedented five full terms under the next mayor, Tom Menino, as a return to an “old electoral pattern,” pulling together different political camps. But Sullivan emphasized the new elements: the change in voter engagement and the imprint of activism on campaigns and governance.

“There is never going to be a mayor of Boston who is not a mayor of the neighborhoods,” he said. “Flynn changed the whole paradigm of what it means to be mayor.”

Walker fondly recalled another change of paradigm that he noticed while spending time in King’s campaign headquarters at Columbia Road and Blue Hill Avenue, right across from Franklin Park. Less than five years earlier, in a front-page story about persistent problems with street crime by teenagers, The Boston Globe had flagged the area as Dorchester’s “Badlands,” during a time when much of the city was still beset with racial strife. In the summer of 1983, Walker found himself with a mix of campaign workers, from Roxbury to East Boston, hand-painting signs and buttons with what emerged as King’s signature rainbow colors.

“I just remember them saying to me, and saying to each other, that they could never imagine on a hot summer night, from all the different neighborhoods, being there and working together and having hope,” he said. “That’s something that had never happened in Boston before.”