August 17, 2023

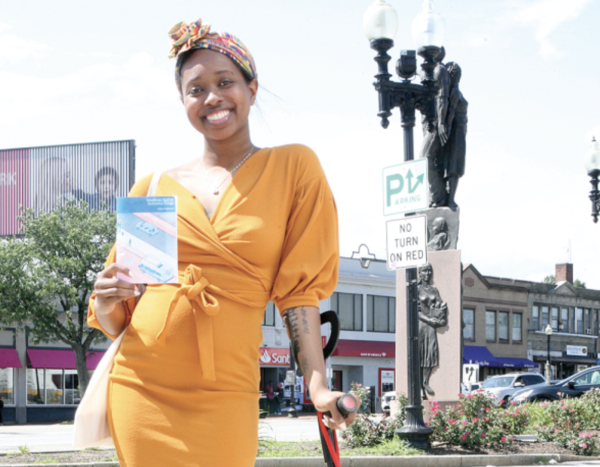

Ellice Patterson in Mattapan Square. (Seth Daniel photo)

Staring down the zig-zagging crosswalks of Mattapan Square on two legs is enough to make a pedestrian want to give up, but Ellice Patterson did it on two knees, crawling slowly as a form of art and protest to highlight how difficult it can be for the disabled – and the elderly – to cross more than a few of the streets of Boston.

The “protest crawl” on June 7 was part of Patterson’s Artist in Residency (AIR) with the Boston Transportation Department (BTD) and was aimed at opening eyes about the challenges within the ongoing Mattapan Square Transportation Action Plan by showing planners and community members the real “barriers to public life” that exist for disabled people at a major nexus like Mattapan Square.

The results spoke for themselves. It took Patterson 45 minutes to get from the eastern side of Blue Hill Avenue over to Cummins Highway then to River Street heading west, and then back to Mattapan Station. She couldn’t make a full circle because there is no crosswalk at the southern end of Blue Hill Avenue.

“If there’s one thing I hope to see at the end it would be the ability to actually make a complete circle here safely,” said the 29-year-old Patterson during an interview in Mattapan Square. “It seems small, but it does have a big impact because when I got to the far side (of River Street) I couldn’t just cross four lanes of Blue Hill Avenue. I had to come back and cross countless lanes and that takes a long time and has a big impact on my ability to get to whatever I have to do on this side of the street.”

As she was speaking to the Reporter, about a dozen people using Rollators, canes, ability aids, and wheelchairs were navigating the crosswalks with difficulty and trepidation. Over an hour’s time, the honking of car horns filled the air.

Project manager Charlotte Fleetwood, who has been instrumental in the Mattapan Square process, described the “protest crawl” as “terrifying” during a recent meeting. She said the action opened her eyes and those of others who use the Square and plan for its future.

Some of the things the protesters encountered that day were broken pedestrian signals that worked against safe crossings, drivers who didn’t acknowledge them crossing while they made right turns, and lots of obscured sight lines and difficult angles for those in wheelchairs. Additionally, the fact that the Square does not have audible crossing prompts stymied a blind activist who was also on the crawl.

“I hoped it would help others to see the very visceral process that someone goes through in navigating the streets,” said Patterson. “The crawl was a representation of how I feel in navigating the streets when I’m out on a day-to-day basis and how coming home I feel more down and inflamed. It was a process to show that and the other challenges that I and others feel when navigating and how it can be a barrier to public life.”

It also left her with quite a few injuries, as the roadway and sidewalks tore into her knees. “I had bruises for weeks,” she said.

She also produced a booklet called the “Manifesto Against Defensive Design,” a guide that she left behind that she hopes will inform city planners working on the Mattapan Square project and others around the city. She believes it could be used nationally as a model of how to rebuild complicated transportation networks.

Patterson,an accomplished dancer since the age of 4, has been in the disability community since 2010 when an operation limited her ability to move. She has continued dancing, however, and now is the full-time director and founder of Abilities Dance, which puts on performances and advocates for the arts.

Originally from Mississippi, she came to Boston 11 years ago and has earned a degree from Wellesley College in Biological Sciences, and a master’s degree from Boston University’s in business management. She is also the former executive director of BalletRox in Roxbury and has her choreography appears on numerous stages in Boston, Chicago, and New York City.

When she came into the AIR program, she said, she took a while to learn what the BTD did, and to figure out what would be appropriate expression. Eventually she decided that a dance piece “didn’t feel authentic,” so she turned to a popular form of protest used by disability communities in the 1980s – a crawl.

Because transportation planners don’t often seek the advice of artists, let alone a disabled one, it was hard for those in City Hall to understand her purpose, Patterson said.

She said that it was challenging at first when she was with people who didn’t understand the vision. Because of her background in dance, they were expecting a sit-down dance performance, so they weren’t as engaged in the process. Later, when they observed the crawl, she said, people had a better realization of her goals. “It would have been nice to see what impact could have been made if I would have had that support throughout,” she noted.

Patterson said she hopes to work with the BTD again in the future to continue to try to make transportation more accessible from the perspective of an artist and a disabled person. She said the artist-in-residence program allows someone like her to potentially change how simple things like streets are designed.

“I think that with more resources, the program definitely has the potential for even more community impact and government change as well,” she said.