September 14, 2023

Celebrating the 40th birthday of the Dorchester Reporter has transported me back to 1983, when Ed and Mary Forry began publishing their newspaper. I was still early in my tenure as executive director of the Codman Square Health Center, which took several years to start up operations after being organized in 1974. In those days, we had appointment books that we kept for telling us what we needed to do on a daily basis, and I was recently able to find my 1983 book for the purpose of revisiting that year. The following is a reflection on the notes in that book.

A page from a special election guide published in the second edition of The Reporter in October 1983 included a map of the newly-drawn District 3.

The year 1983 was one of a string of several years during which both Boston and Dorchester started reviving economically. The exodus of residents by some 10,000 per year on average since the city’s peak population of 801,444 in 1950 had ended, and the numbers were beginning to increase, much of that due to immigration largely into Dorchester and Roxbury of Vietnamese, West Indians, Latin Americans, Cape Verdeans, Africans, gays, and what we called “young urban professionals.” This effectively abated the effect of the arson fires in the 1970s, which was the product of loss of population making much of the housing stock unnecessary. In short, the increase in population started expanding the housing market. The dedication of new housing at Norfolk Terrace near Codman Square was a harbinger of things to come.

The fallout from the desegregation order of 1974 and resultant boycotts had also abated, though the school population had dropped by 40,000. Unfortunately, neighborhood violence did not ease off. With racial violence continuing, several efforts to stem the violence were convened, including one called the Dorchester Task Force, which sent teens of color and their white counterparts to Hurricane Island in Maine to participate in month-long Outward Bound programs together. My appointment book has dozens of entries for Task Force and youth council meetings, and other public safety sessions.

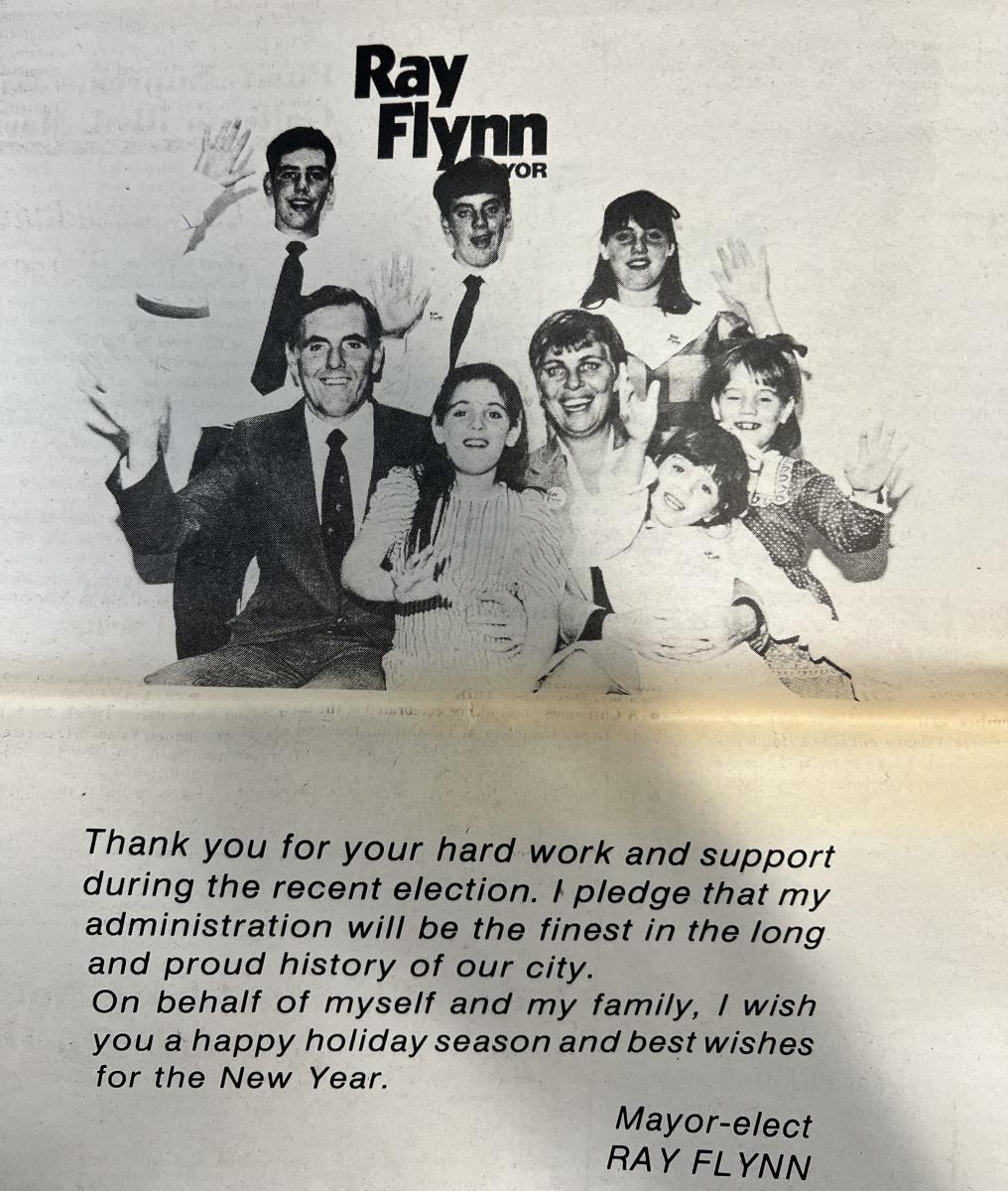

It was in 1983 that Kevin H. White stepped down after sixteen years as mayor, resulting in nine candidates, including some major political figures, running to succeed him. City Councillor Ray Flynn ultimately won, beating former state representative Mel King in the final. My book was filled with various candidate events and press conferences.

An advertisement in the December edition carried a message from the “Mayor-elect.”

At the Codman Square Health Center, then located in the basement of what is now the Great Hall, I gave up my office to create a dental clinic and moved into the handicap toilet, the only space available to me at the time. With new grants funding behavioral health and nutrition services, the health center appealed to City Hall, which owned the building, to allow it to expand into empty space on the main floor, where my office could also be relocated. City Hall did not respond, so one weekend, a group of ten health center volunteers, working with housing innovator Pat Cooke to build offices in the space and the health center, just moved in. It’s hard to picture that happening today, but health centers, which had difficult relations with the White administration, saw themselves as participants in the health care revolution in those early days.

One health care reform with many meeting entries in my book that made a splash and then died was called the Commonwealth Health Care Corporation (CHCC), an attempt by the teaching hospitals of Boston to control Medicaid dollars by moving Medicaid recipients into managed care plans. Run by Rena Spence, who eventually formed a chain of women’s health centers, its board included the presidents of all of Boston’s teaching hospitals. They assumed that the health centers would just join in, but the centers demanded 50 percent of the vote on decisions by CHCC. They held out, and, eventually, the hospitals caved, giving health center representatives half of the seats on the board.

Pancho Chang, then head of South Cove Health Center, asked Jerry Grossman, head of New England Medical Center (now Tufts Medical Center) and chair of CHCC, why they caved, to which Grossman replied, “When LBJ won the ‘64 election, his VP, Hubert Humphrey, told him, ‘Now we can fire [FBI Head] J. Edgar Hoover,’ to which Johnson replied, ‘Now, Hubert, you know people like Hoover are always gonna be pissin’, and it’s better having him on the inside pissin’ out than on the outside pissin’ in.’”

In the end, the Commonwealth Health Care Corporation didn’t survive and turning the Medicaid population over to the teaching hospitals would have to wait a few decades more.

The MBTA also changed the name of the Red Line’s Columbia Station to “JFK/UMass Station” that year. My appointment book had several meetings with Dan Fenn of the Kennedy Library in its pages. The Columbia Savin Hill Civic Association (CSHCA), of which I had been elected president, had studied the guidelines for MBTA name changes, which stated that the first line on a station’s name should be the name of the neighborhood, with the second line being institutions within the neighborhood. Given that, we advocated for keeping the Columbia name and adding JFK and UMass to the second line.

The Kennedy Library leadership, which included Fenn and Dave Powers, who had worked with JFK, were incensed that the neighborhood would oppose JFK being on the first line and tried to make a deal in one of the meetings to rename the station “JFK at Columbia” and I told them that I’d have to bring that idea back to the civic association, which voted to continue to suggest that the MBTA follow its own rules. The Library and UMass pulled political strings and the T violated its own rules in the renaming. Fenn followed his victory by sending me a stinging letter saying that I needed to learn how to interact with the powerful.

That was just the beginning of CSHCA’s difficult interactions with the MBTA. That year began the fight over moving the interchange that brings the tracks of the Braintree and Ashmont lines together from before the Andrew Square tunnel to a location before Savin Hill Station via building something called the “Savin Hill Flyover,” which would have given Columbia and Savin Hill stations access to both lines. That account runs much longer and will be told in a later column.

These are some of the stories that have resurfaced from my perusal of my appointment book. Dorchester in 1983 was emerging from some pretty difficult times when arson, violence, and racial conflict dominated the news. But the sheer volume of community activity showed a higher level of hope in its future, all covered by The Reporter, the best community newspaper in the USA.

Bill Walczak is the former director of the Codman Square Health Center and a Reporter columnist.

This article has been edited to correct an error in reference to the 1968 presidential election that was included in the original article. Lyndon Johnson was elected president in 1964, not 1968. Richard M. Nixon won the '68 election.