February 14, 2019

Last year’s reform law expanded process

Massachusetts residents with a history of criminal activity or court appearances are increasingly seeking to seal or, even better, expunge their records to improve their odds of gaining access to employment, housing, and educational opportunities.

Now, as lawmakers consider even less burdensome rules for those looking for relief, there is a renewed push by advocates to get more people into the pipeline through a series of workshops at courthouses in Dorchester and Roxbury.

The workshops, led by Greater Boston Legal Services (GBLS), advise individuals on how to go about sealing their Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) from public notice; they also counsel clients about the process for expungement, which essentially destroys the paper trail of their cases.

According to US Department of Justice statistics, there were 1,572,600 people in the state’s criminal record history system as of 2016. A Harvard survey, which followed 122 newly released people from 2012 to 2013, found that six to twelve months after they were released, only a little more than half had paid employment and 35-43 percent lived in temporary housing. The survey also found that black and Hispanic ex-prisoners earned less than their white counterparts.

“We still have remnants of the so-called war on drugs even though the tough-on-crime mentality doesn’t reduce crime,” said Pauline Quirion, director of GBLS’s CORI and re-entry project. “What reduces crime, as the studies show, is having employment and substance use treatment when you need it.”

In the wake of last year’s criminal justice reform law, Massachusetts allows a felony record to be sealed seven years after someone is found guilty or released from incarceration. The waiting time for a misdemeanor offense is three years.

To seal a record, a petitioner first must get a copy of his or her CORI report from the Department of Criminal Justice Information, then, after a period of review, file a form with the Office of the Commissioner of Probation. Alternatively, a petitioner can gain a sealing order if he or she goes directly to court and wins a ruling.

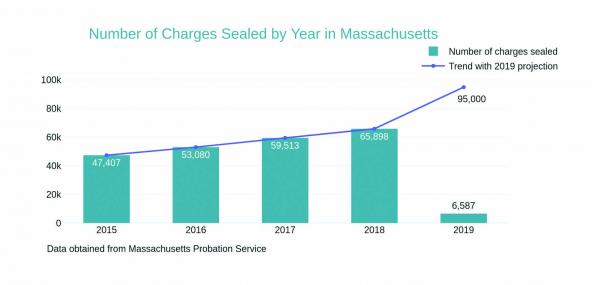

The number of sealed records has been increasing in the last four years, and 2019 is expected to see as many as 95,000 charges sealed, official data suggest.

“When I first moved to Boston, people were talking about this evil ‘CORI,’ and I thought, who is she? I don’t want to meet her,” said Horace Small, founder and executive director of Union of Minority Neighborhoods.

Small, a member of the state’s Cannabis Advisory Board, said some of the people who have criminal records during the war on drugs deserve a second chance. “We had people who lost the opportunity to go to college, get a home, and get into the military simply because they had a joint in their pocket. We have to give people who are most affected by the injustice of the criminal justice system, aka, the black and brown people, their good names back.”

Darrin Howell, a community and political organizer who ran for state representative last year, served a one-year sentence in the early 2000s. Before prison, he worked at an administrative job in Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. But with a CORI, he said, he could only find jobs in manual labor.

He later worked in a seasoning packing warehouse, a moving company, Boston Scientific Corporation, and a medical device warehouse, before he was hired on staff by former city councilor Chuck Turner.

Howell said he was hired once through a temp agency for a two-week assignment for Partners HealthCare that was extended to three months. Eventually, the company wanted to hire him permanently, he said, but in the end, it fired him after finding out he had a CORI.

Howell thinks different levels of offenses should be dealt with differently. “I have a CORI. I know your policy is zero-tolerance, but as you can see, my CORI has nothing to do with the work I was doing,” he said.

Even when a court case ends in an individual’s favor for sealing, it will still be on a CORI sheet. Ernest, who spoke to the Reporter and asked that only his first name be used, had a CORI that included three serious charges, but no convictions. Still, the records led to him being turned down from job applications sent to Uber, Lyft, and some private security companies. The South End resident tried to seal his records in the district courts in Chelsea and East Boston to no avail. He was told that the public has the right to know his record.

Ernest said Pauline Quirion took his information over the phone and later got him a date in Roxbury Municipal Court, where he filed the petition and had his records sealed. He now works as a security officer.

The expungement process is more complex for those seeking relief. Eligibility is limited to cases that happened before the person’s 21st birthday, to mistakes in judicial proceedings, and to cases where the offense has been decriminalized.

State officials said this week that since the reform legislation went into effect last October, 82 petitioners have had their records expunged.

Geoff Foster, the director of organizing and policy with UTEC, a Lowell youth organization, said that none of the young people in his organization or partner organizations have been able to expunge their records because only people with a single court case on the record are eligible to get their records erased.

UTEC offers employment to people aged 17 to 25 who are returning to the community from incarceration or were involved in gangs, and is part of Teens Leading the Way, a statewide youth advocacy coalition with different organizations. Teens Leading the Way is advocating for a new bill that will expand people’s eligibility to expunge records they received before 21.

State Sen. Cynthia Stone Creem, a sponsor of the bill, said that “providing the opportunity to expunge juvenile records and remove the stigma of such involvement is a critical component to the future success of justice involved youth.”

A community organizer who has served time and has an open CORI told the Reporter that having a criminal record shouldn’t stop one from trying to find employment or housing.

In his work, he helps ex-offenders get GED, connects them with shelters if they are homeless, and introduces them to employers who are willing to help those with CORIs.

“It’s a tough battle, when you first get out of incarceration,” he said. “A lot of people shy away from employment and education. They want to [learn and work], but sometimes they say, ‘I have a CORI, and therefore nobody’s going to hire me,’ which is not true.”

He hopes more people will be open to hiring ex-prisoners. “If they did the time and they paid their debts to society, then why not give them a second chance? What are you so fearful for? ... How can you help this person not go back to jail?”

GBLS hosts walk-in clinics in Dorchester court on the second and fourth Wednesdays of the month, and in Roxbury court on the third Thursday every month, except for holidays.