January 28, 2021

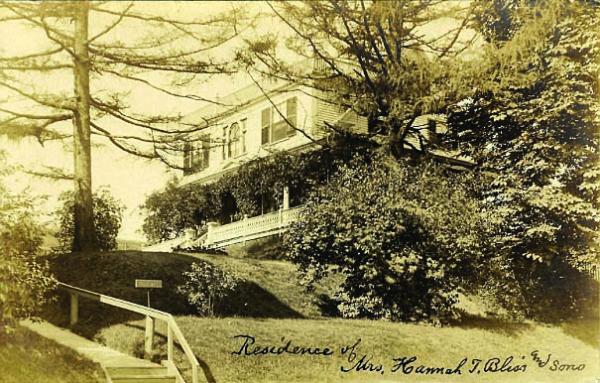

The Hannah Bliss home that was torn down to make room for Ronan Park. Dorchester Historical Society photo

Boston archeologists have unearthed a trove of historical details about a sinkhole that opened up in early December near a pathway in Ronan Park. At the time, a cursory investigation (involving an iPhone and flashlights taped to a paint roller) revealed the existence of a well that was likely built sometime in the 1800s. Only one “artifact” was found — a plastic liquor bottle probably tossed into the hole within days of its opening.

However, a report released on Jan. 22 by the Boston City Archaeology Program provides a fuller picture of the lives of some of the people who lived on the land encompassing the well.

In reading the report, one gets the sense of starting down the deep well of Boston’s history, and in the darkness seeing hints of the ugly realities of the time, such as the colonization of indigenous lands, patriarchal laws, and deadly diseases. But one also gets a glimpse of how the land that we call Ronan Park came to be what it is today.

Although Ronan Park has never been surveyed archaeologically, the report stated, it is likely that some indigenous sites exist or once existed in the park, as Boston as a whole is part of the ancestral homelands of the Massachusett. The closest intact sites are at Savin Hill and Commercial Point, both Massachusett burial places that date to the 17th century.

In 1630, European immigrants began colonizing the area just north of the site. And in 1793, historical records show, Thaddeus Mason Harris, a minister of the Dorchester First Parish Church located just north of Ronan Park, bought the land on which the site sits.

In 1818, a bricklayer named John Pierce purchased 10 acres of the land and built two homes for himself and his wife, Catherine B. Pierce, and their family — the second one at 151 Adams St., on land where the well was found.

John’s son, Charles, later married Mary Lyman of Springfield, in 1846. And by the 1850s, both appeared to be living in a house near 151 Adams St., along with their two children, a couple of Irish laborers, and two Irish-born women, Kate Fitzgerald and Margaret Kohn, who, the archeologists suggest, may have been domestic servants.

In 1857, Charles died of typhoid fever but didn’t leave a will, and in the years that followed, Mary apparently fell on hard times. By law, she had to petition for an allowance from her husband’s $43,000 estate. And the $355 she was awarded apparently wasn’t enough for her and her two children to live on. The 1865 state census found her living in a boarding house south of Fields Corner, along with 22 other people.

Later, Mary purchased the property at 151 Adams St., which had been willed to various family members by her husband’s father, John. Among the heirs whose stakes in the property she had to buy up to obtain title? Her son, Charles Jr., and her daughter Elizabeth.

Mary died of cancer in November 1885. In her will, she left $1,000 to her neighbor, $100 to her servant, and $50 to her nurse. Her daughter was left the Adams Street house, and the rest of her $18,000 estate — unless she married.

Elizabeth died from kidney disease in 1892 and was buried at Mount Benedict Cemetery in West Roxbury. And while she remained unmarried and did not have children, the report states that «Elizabeth’s will and probate reflects a social life filled with family and long-time friends.” She named 28 people in the will.

The report goes on to state that in the will, Elizabeth made “a clear preference for the women in her life, with 20 women named … and just nine men, and the women received the vast majority of her estate, totaling nearly $30,000, with just $5,000 given to men.”

In 1893, the executors of Elizabeth’s estate sold the property to Hannah Bliss for “one dollar and other valuable considerations to us” — although historians do not know much about why or what that meant.

In 1910, at about 82 years old, Bliss died of a cerebral hemorrhage. And her heirs sold the property to the city of Boston, which later included it in the construction of Ronan Park.

There are more depths to plumb in this report, if you are a nerd for that kind of thing — from geologic analysis to analyses to the history of waterworks in Boston. See DotNews.com for a link to the full report.

This article was first published by WBUR 90.9FM on Jan. 24. The Reporter and WBUR share content through a media partnership.