December 18, 2023

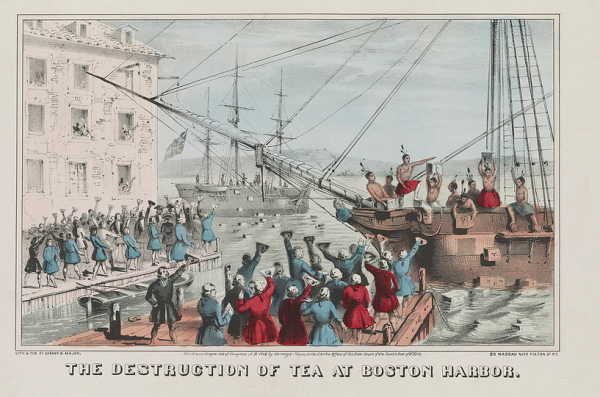

Image courtesy Library of Congress.

Last Saturday was a major anniversary for the Boston Tea Party, which happened 250 years ago on December 16, 1773. The Tea Party was a major escalation in the era’s conflict between the American colonies and the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

What was at that time a movement that mainly saw Parliament rather than King George III as the problem rapidly changed following the Tea Party. Thirty months later, the colonies, calling themselves the “thirteen united States of America” declared their independence, giving as their reason the king’s “repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

We’ve all learned the American side of the Tea Party story in school. It has been fascinating learning about the British side of the story from reading “The Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson,” who was the royal governor of the Massachusetts colony at the time of the Tea Party. His communications from 1773 indicate that tensions between the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Parliament in London were growing, mainly due to decisions by the British that colonists believed usurped their authority to govern themselves.

Hutchinson, deciding that he had to take a stand against the view that the colonists could challenge the supremacy of Parliament, summoned the Massachusetts General Court into session and stated, “I know of no line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies.”

Colonist leaders Samuel and John Adams countered that the relationship with Britain was a contract between the colonists and the king, not Parliament, and, therefore, the Massachusetts General Court, not Parliament, was the entity that had the authority to determine which British laws would be observed in the colony.

In this atmosphere, Parliament’s introduction in the fall of 1773 of the Tea Act, which was meant to support a financially troubled East India Company, became the next crisis. Hutchinson, who lived in downtown Boston and had a country house on Milton Hill where today’s Hutchinson’s Field is located, viewed the group of Boston radicals led by Samuel Adams as the cause of the tensions between Britain and Massachusetts. He believed that overall, the general population was loyal to rule from London.

With the Massachusetts economy in good shape and local taxes low, Hutchinson couldn’t understand why there would be such opposition to a small tea tax. But the issue for the colonists was, essentially, local control versus control by a faraway legislature exerting more and more control over Massachusetts.

Boston leaders initially tried to get merchants who would be receiving tea shipments to resign their offices, with the result that no one would be available to accept the tea. But that didn’t work, and ships with tea started arriving in Boston on Nov. 28. The law in place stated that the tea tax had to be paid within twenty days of arrival in port, that is, by Dec. 16, or the cargo would be subject to confiscation.

Various plans were developed to either have the tea kept by the government or to have the ships leave before the twenty-day deadline, but bureaucratic rules kept the vessels from leaving Boston. Hutchinson pleaded with Lord Dartmouth, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, to allow the tea to be sent elsewhere, as “the spirit is now much lower in several other Colonies.” He even suggested that war with Spain or France could be “the means of bringing the people to their senses.”

Correspondence from Hutchinson on Dec. 14 shows that he tried to get another town in the area, including Dorchester, to allow the ships to unload the tea there, but “they have kept a constant military Watch of 25 men every night, generally with their fire arms, to prevent the Tea being privately landed.”

Two days later, on Dec. 16, a messenger from the Boston “Body of the Trade” went to Hutchinson’s house on Milton Hill with a request that the governor grant passes for the ships to leave Boston. He refused, and reported to Lord Dartmouth the next day that “yesterday towards evening [the messenger] came to me at Milton, and I soon satisfied him that no such permit would be granted until the Vessel was regularly cleared. He returned to Town after dark in the evening and reported to the Meeting the answer I had given him.”

The “Meeting” he was referring to was a huge gathering called due to the imminent tea tax payment deadline. It was held at the Old South Meeting House, attracting at least 5,000 people (about a third of the population of Boston), who surrounded the Meeting House due to the sheer size of the crowd.

Upon hearing the response from Hutchinson, Samuel Adams declared, “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country,” and a group of men proceeded to go to three of the ships and dump 340 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

In retaliation, Parliament responded with the Boston Port Bill, which closed off the harbor to commerce by ship and required Bostonians to pay for the tea dropped into the harbor. Hutchinson fled to England and was replaced as royal governor by General Thomas Gage. Other acts of Parliament, meant to stop resistance to its supreme authority, followed. Colonists called them the Intolerable Acts and they served to increase tensions and radicalize even more Massachusetts residents. Even so, the colonists still saw the problem as parliament, not the king. It would be another year or so before George III became the primary villain.

Reading through Hutchinson’s missives shows so many missed opportunities to resolve the issue. Would Hutchinson have brusquely dismissed the messenger if he knew there were 5,000 angry Bostonians waiting for his decision?

My exploration of this topic prompted some thoughts about all the other missed opportunities to resolve the conflict that led to the American Revolution. What would have happened if Parliament had decided that problems with the colonies wasn’t worth the money they would get from taxation, and allowed the colonies to return to control of their own local affairs? Would the colonies then have remained part of the British Empire, rather than establish the United States of America?

And what would have happened after Aug. 1, 1834, when Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which outlawed slavery across the British Empire, freeing 800,000 enslaved people in its colonies? Would there have been acceptance of abolition by an America still ruled by the British government, avoiding the deaths 31 years later of 632,000 Union and Confederate soldiers?

Speculative history has produced popular television shows for a reason: Our world could easily have turned out differently had just a few issues had been resolved in another way. That’s why history needs to be taught with honest appraisals of how crises are handled. In the words of the turn-of-the-19th century Harvard intellectual George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Bill Walczak lives in Dorchester. His column appears regularly in The Reporter.